Board games might involve a race to a finish line, as in Sorry! or that ubiquitous first board game for kids, Candyland. Or they might entail a strategic battle for dominance, as in chess or checkers. Some have simple rules (think Clue), while others have a headache-inducing learning curve (such as Feudeum, in which players control a set of medieval characters who must survive in a complex economy).

Whether you like to while away long hours with Monopoly or a quick Snakes and Ladders is more your speed, you’re taking part in a tradition that stretches back millennia. Here are 10 of the oldest board games and a quick primer on how to play each one. With these games, you may find new (ancient) ways to fill the long summer days.

[Play science-inspired games, puzzles and quizzes in our new Games section]

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

An inlaid game board and playing pieces discovered in a tomb at the southern Iraqi site of Ur. They date back to the second millennium B.C.E.

Zev Radovan/Alamy Stock Photo

1. The Royal Game of Ur

First played: As early as 2600 B.C.E.

Who played it: Ancient Mesopotamians. The game also spread around Central Asia, from Iran to India.

The backstory: No one knows what the people who invented the Royal Game of Ur called it. Modern archaeologists named this game after the site in southern Iraq where the boards and pieces were found in the 1920s. The game was played until at least around 177 B.C.E., but it may have persisted into the 20th century among the Jewish community of Kochi, India, says Walter Crist, an archaeologist and lecturer at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who studies ancient games. Some snippets of the rules are known from ancient texts that describe the game’s distinctive I-shaped board but don’t say the name of the game, which, Crist notes, “would have been nice.”

The rules: Each of the two players has five or seven buttonlike pieces. They throw dice to enter these pieces onto the game board, where they try to beat their opponent in moving all their own pieces to a square at the end of the board. Some squares are marked with symbols denoting them as safe, while others are “combat” squares, where players can capture their opponent’s pieces and send them back to the starting square.

Can I play it today? You can get your own version of the Royal Game of Ur for less than $20 online.

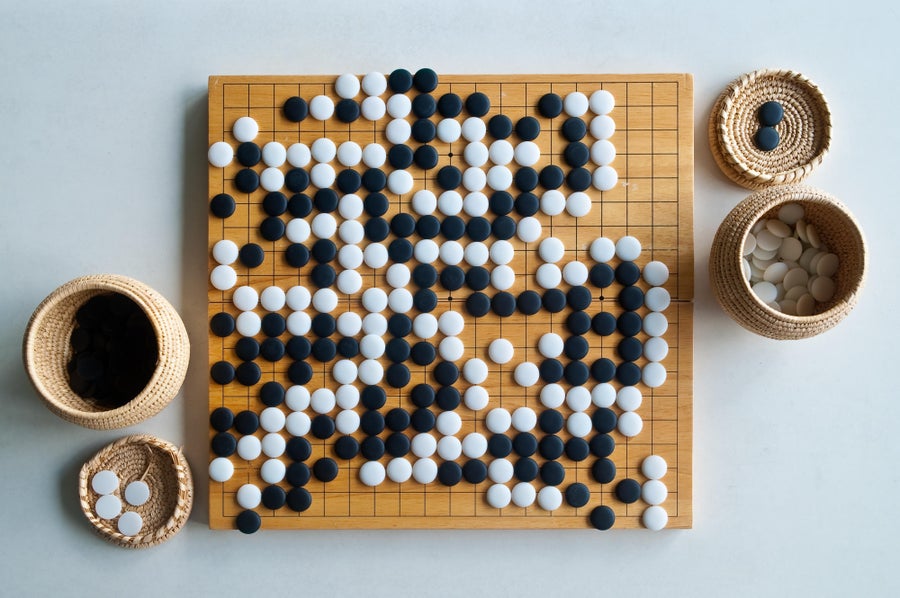

An example of a Go board at the end of a game between two people.

Saran Poroong / Alamy Stock Photo

2. Go

First played: Around 500 B.C.E.

Who played it: The ancient Chinese, who also spread the game throughout Asia.

The backstory: Myth and legend hold that a Chinese emperor named Yao taught his son Dan Zhu the game of Go as early as 2100 B.C.E., while other tales trace the game to the mythical Yellow Emperor Huangdi. The oldest archaeological evidence of the game dates to the last few centuries B.C.E., however, Crist says. “It’s basically the oldest of the traditional board games that are really still popular today,” he adds.

The rules: Go is played on a 19-by-19 board of squares. Each of the two players gets a supply of stones (181 black pieces or 180 white ones) and must place them on the board in turn. The goal is to surround the other player’s stones to win more of the board’s area. The player with the most area wins.

Can I play today? Oh, you can play all right. Go is a massively popular strategy game with associations dedicated to its play around the world. Even computers are in on it: in March 2016 artificial intelligence AlphaGo beat champion Go player Lee Sedol in a highly publicized match.

One of at least four Senet boards that were found buried with King Tut.

Smith Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

3. Senet

First played: Around 3000 B.C.E.

Who played it: Ancient Egyptians.

The backstory: Senet was popular in Egypt up through the Roman period. Everyone played, from guards in temples who scratched game boards into the ground to kings who were interred with Senet boards in their tombs, Crist says.

“Pharaohs, commoners—everybody knew the game,” he says.

Ancient Egyptian texts sometimes refer to the game as a metaphor for moving through the afterlife, Crist says, so it may have sometimes had religious connotations. This religious meaning tied the game very closely to Egyptian culture, says Barbara Carè, an archaeologist and senior lecturer at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. Such deep cultural meaning may be why some games gain popularity locally but don’t spread too far abroad, she says. “You can move the game somewhere else, but it doesn’t have the same meaning,” Carè adds.

The rules: Each of two players moved at least 10 pawns around a 30-square board and may have determined the number of spaces to move by throwing sets of four two-sided sticks. Fragments of texts and tomb paintings suggest players could block or pass each other, Crist says, but the details are unknown.

Can I play today? You can try. Timothy Kendall, author of Passing through the Netherworld: The Meaning and Play of Senet, an Ancient Egyptian Funerary Game (Kirk Game Company, 1978), attempted to reconstruct Senet’s gameplay. Historian R. C. Bell also came up with a version. Would ancient Egyptians recognize these rules? Who knows.

A reconstruction of the ancient Greek board game pente grammai.

4. Pente Grammai

First played: Earlier than 600 B.C.E.

Who played it: Ancient Greeks.

The backstory: Pente grammai, or “five lines,” is an ancient Greek board game whose original name and rules have been lost. The game is known from poems, texts and ancient boards that consist of five parallel lines, each with a small dot or divot at each end. The game was associated with men, strategy and heroics, Carè says. It’s most famously depicted in a painting on a vase, reproduced many times in Greece around 500 B.C.E., showing the heroes Ajax and Achilles playing a tense round. Women weren’t depicted playing board games in ancient Greece, Carè notes, because of the association of games with male pursuits. In ancient Rome, however, the connotations were different. Women are often depicted playing board games alongside men in ancient Roman paintings, Carè says. “This is again symbolic,” she says, “but it’s a matter of seduction” rather than military strategy.

The rules: The details are sketchy, but two players competed, each possibly holding five pieces. The middle of the five lines was known as the sacred line, and the goal was to land one’s pieces on that line. The players threw dice to determine their move.

Can I play today? There are various reconstructed rules of the game, but how close they are to the ancient Greek version is hard to determine.

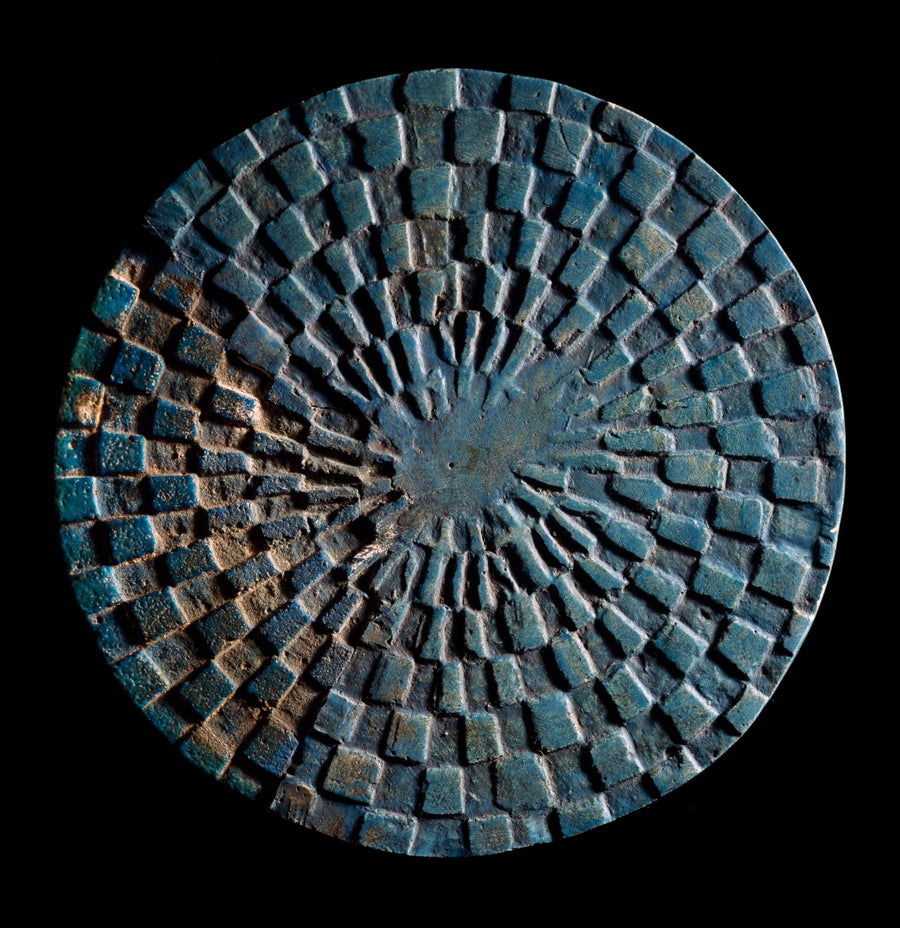

A Mehen board discovered in the tomb of the pharaoh Seth-Peribsen at Abydos in Egypt. The spiral board looks like an abstract coiled snake.

5. Mehen

First played: Before 3000 B.C.E.

Who played it: Ancient Egyptians for about 1,000 years.

The backstory: Mehen is one of the oldest games we still know the name for, Crist says. The board was a spiral, akin to an abstract rendering of a snake. And different examples of that board had different numbers of spaces. The game could be played by up to six players. That made it unique among ancient board games, which tended to be two-player affairs, Crist says.

The rules: Each player had six marblelike pieces and two lion-shaped pieces. Based on modern games from Saharan Africa, the goal may have been to get pieces to the center of the board and back, with the lion pieces perhaps acting to prevent one’s opponent’s pieces from returning safely. “Whether or not this is the way the ancient game was played is not something we can really say,” Crist says, because there are 4,000 years between when ancient Egyptians quit playing the game and when modern people started.

Can I play today? Likely the closest you can get is to play Hyena Chase, or the Hyena Game, which is also known as Li’b el-Merafib in Sudan.

A game board of Hounds and Jackals shows the sticks with jackal or dog heads that players would have moved.

Cultural Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

6. Hounds and Jackals

First played: Around 2000 B.C.E.

Who played it: People all over western Asia and Egypt.

The backstory: This game pops up across western Asia and Egypt around the same time, Crist says, so it’s unclear who invented it. Egyptologist Howard Carter gave this game its modern name; no one knows what ancient people called it. There were different variations of the game board across time and space, with a wider variety of gameplay in western Asia than in Egypt, Crist says.

The rules: Players moved sticks with either jackal or dog heads through two tracks made up of 29 holes each. No dice have been found, Crist says, but they must have existed. Most likely, the goal was to get one’s pieces to a hole at the end of the game board that was often either specially marked or larger than the other holes.

Can I play today? Game boards with modern-day reconstructions of rules are available, but no surviving text describes how the game was originally played.

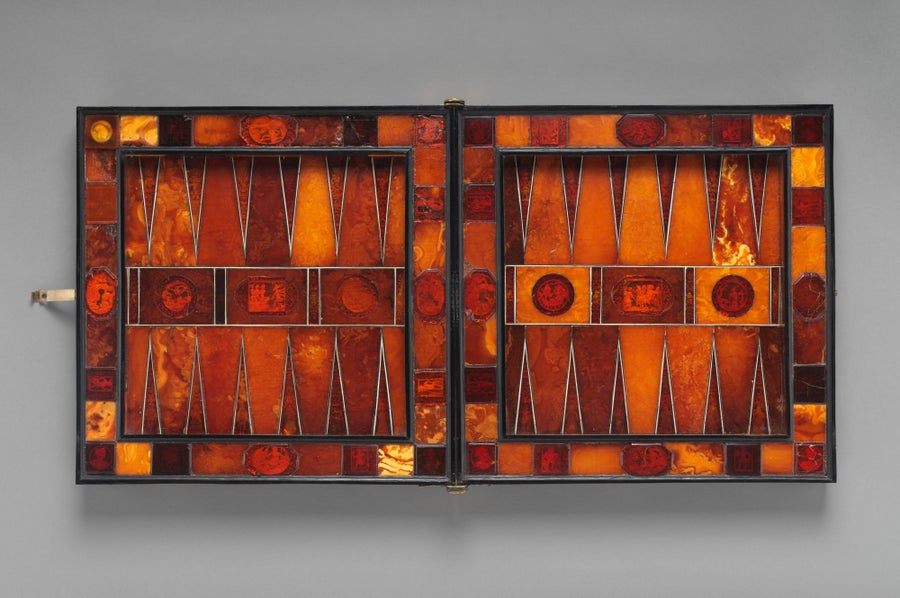

A game board that could be used for playing backgammon, chess, a French variation of backgammon called trictrac and a dice-throwing game called goose.

Gift of Gustavus A. Pfeiffer, 1948/Metropolitan Museum of Art

7. Backgammon

First played: Great question!

Who played it: Persians, Ancient Romans, or maybe other Central Asians.

The backstory: Dating the origins of games is often a tricky business, Carè says. Graffiti game boards are often more recent than the buildings or pavements they’re etched into. In ancient Greece and Rome, for example, many buildings that were located in solemn religious regions in the classical period (between the eighth century B.C.E. and the fifth century C.E.) were, in later centuries, decorated with gaming boards etched into the facades. This fact is interesting as far as elucidating how people used a space, Carè says, but can make it hard to determine the true age of a game board.

Backgammon is a good example of a game with a clouded origin. Some argue that it traces back to a Roman game called ludus duodecim scriptorum, or “game of 12 lines,” Crist says. Others say it was invented in Persia, where it was first known as nard. Archaeologists have found game board graffiti of backgammon from the early eighth century C.E. in what is now Iran, Crist says.

The game likely spread to Europe when Crusaders encountered it during the 10th and 11th centuries.

The rules: Players each get 15 checkers and a pair of dice. The goal is to move all checkers around and off the board along a horseshoe-shaped path.

Can I play today? Backgammon is a standard in game cabinets around the world. A version called tavli is the national game in Greece and Cyprus.

Illustration of a patolli game being played.

The History Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

8. Patolli

First played: As early as 200 B.C.E.

Who played it: Ancient Maya, Ancient Aztecs and other Mesoamerican groups.

The backstory: Patolli, or patole, was played across Central America and southern North America up into what is today Oklahoma, Crist says. Much of what is known of the rules come from the records of Spanish conquistadors who encountered it during their besiegement of the Aztec Empire in the 1500s.

The rules: Players moved six pieces across an X-shaped board and used a handful of marked dried beans as dice. When a player moved all six pieces around the board before their opponent, they won the round. Patolli was a gambling game, so winners got to take wagered items such as blankets or food from the loser of each round.

Can I play today? Tūhura Otago Museum in New Zealand has a printable game board and reconstructed rules.

A replica of the historic Viking board game hnefatafl.

9. Hnefatafl

First played: Popular during the Viking Age in Europe, after C.E. 600, but likely derived from a Roman game called ludus latrunculorum with roots in the first century B.C.E.

Who played it: Famously, the Vikings. But versions of hnefatafl, or tafl, games were found all over northern Europe. The Sámi people of northern Scandinavia played a version called tablut as late as 1732.

The backstory: Romans brought early versions of tafl to the “barbarians” along the frontier of the empire, and the games spread and were adapted with different rules over time. Game pieces could be quite elaborate: In 2019 a dig led by the community archaeology firm DigVentures and Durham University in England turned up a candylike game piece at an early medieval monastery on the isle of Lindisfarne. Made of blue glass and decorated with white swirls and dollops, the piece dated to before C.E. 793, when the Vikings raided Lindisfarne, says DigVentures archaeologist Maiya Pina-Dacier.

“We know the Vikings played another branch of the game,” Pina-Dacier says. Had the Vikings not arrived at Lindisfarne with the intention of razing the place, she says, they might have all played together.

The rules: One player took the role of the king and his army, starting with their pieces at the center of the board, with the exact starting positions differing depending on the version of the game. A second player acted as a surrounding army. The player with the king attempted to get him to the side or corner of the board, while the other player attempted to block the king’s escape.

Can I play today? You sure can. When Pina-Dacier and her colleagues realized they’d found a rare king piece from this ancient game, they immediately ran out to buy and try modern sets, she says. “It’s a really good, fun game, and I would recommend people try playing it,” she says.

A painted and inlaid chess board found in India and dating to the late 17th century. Ashtapada was a precursor to chess.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

10. Ashtapada

First played: Strictly speaking, ashtapada can be used to describe an eight-by-eight board as well as a game played on such a board. The first reference to the game comes from the Buddhist games list, a sixth- or fifth-century B.C.E. list of games that the Buddha purportedly would not play.

Who played it: Not the Buddha. Other ancient Indians seemed to enjoy it, though.

The backstory: Ashtapada is notable because it provides the substrate for chess; early sources describe chess as being played on an ashtapada board, Crist says. One game played on the ashtapada board involved moving pieces in a spiral toward the center, though other games may have used this board, too. Chess showed up around C.E. 600 and supplanted whatever came before as the most wildly popular use of the ashtapada board.

The rules: Players moved an even number of pieces around the board from outside to inside, probably using dice to count their moves. The details of the gameplay have been lost, however.

Can I play today? Plenty of board game enthusiasts speculate about the rules online and make up their own theoretical paths for gameplay. But if you like games with agreed-upon rules, you’re better off joining the seventh century and learning chess.