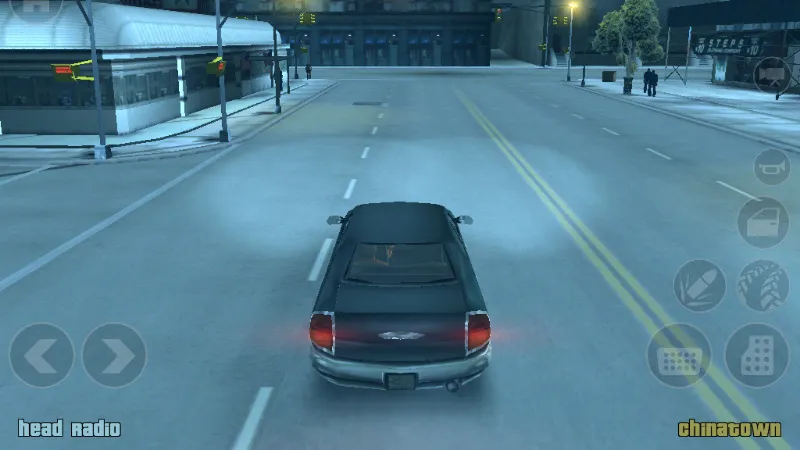

In October 2001, Rockstar Games released Grand Theft Auto III – and the entire pop-culture paradigm shifted. It’s hard to say anything about GTA III that hasn’t been said a million times over the last 20 years, but suffice it to say, it laid a blueprint for open-world games so complete that the game industry still largely follows it today.

To celebrate the game’s 20th anniversary, we recently talked to Rockstar North art director Aaron Garbut over email about his time working on GTA III, what it meant for Rockstar as a company, and its overall legacy in 2021.

Game Informer: How did DMA/Rockstar evolve its technology to the point where GTA III was possible?

Aaron Garbut: There was no evolution technology-wise. Grand Theft Auto III was a new team in a new studio, excited by the possibilities of newer consoles and pushing to create an immersive world in 3D. We didn’t build this on existing technology but grew it from the ground up over the life of the project.

We just wanted to build a world that was as alive and open as we could make it and give players the toolset and flexibility to explore and play in that world. We built narrative and game flow structures to push them on a path and give them direction, but fundamentally it was openness and player freedom we were excited by. The challenge we were trying to solve – and are still working on – is fundamentally, how do we build a place that’s interesting to exist in and give the player enough toys and systems to interact with and mess about? There are clear technical challenges with that – building a diverse, large urban world, and ensuring that it would stream in so that we could build in the variation and scale we wanted. The fact that we wanted it to feel alive and to feel as much as possible like the player existed in it – rather than at the center of it – meant we needed to have the world active even when the player was on a mission or causing chaos. We needed systems that were as solid as possible, and that could also scale in complexity. Fundamentally, we designed what we thought we wanted to play ourselves, and then we figured out how the hell to make it.

GI: Do you remember any of the earliest iterations or prototypes you saw of GTA III?

AG: When we finished our first game at DMA Design, we had some time to prototype and come up with ideas. We also got access to a couple of Dreamcast devkits. Over several weeks, we managed to create a number of blocks of a city with docks, retail areas, and brownstones. We were playing, really, but we added characters walking the streets and cars driving around.

I think we got into some conversations with some of the original GTA code team about GTA in 3D and got dismissed as being too complex. They had been working on some experiments pushing the camera back a bit in the old GTA engine, but that was very far away from where we were trying to go. We were enjoying ourselves; we were young and arrogant and made a conscious decision to redirect the project to be GTA – we knew we could do it, and it had a lot more appeal to us.

During those early days, shortly after we had moved to Edinburgh, we would meet regularly with Sam [Houser, co-founder of Rockstar Games], who had been desperate to move GTA to fully 3D for a long time. We had known him from the last project we had worked on, but we got a lot closer quickly during the early days of GTA III. We were all very in sync right from the start. We’re still largely heading in the same direction we started on way back then.

GI: 20 years later, what do you think is the overall legacy of GTA III?

AG: I think GTA III was a glimpse into what was possible in open-world games. It showed that games could be more about the player than the designer – that we could build worlds of ever-increasing diversity, granularity, and complexity, and create complex systems that players could interact with. That we could stop thinking about levels and start thinking more about worlds, about cohesive spaces, with characters living inside them alongside our player. That we could fill these worlds with interest and leave it for the player to discover and interact. That we could build toys and tools, worlds and systems for the player to play with. But also, that more than all of those things – more than the toys, the living, breathing world, the systems and the like – that we could create a sense of place and the players could be happy just to be. To sit in their car, listen to music, and watch the sunset. It was the idea that with the right complexity and believability comes variety, not just in what the players can do but what they want to do. If the world is complex enough, it exists to pull players into it to experience such a breadth of content and possibility that the players themselves define what they can and will do. That’s a long way from what games were before GTA III, but it’s a journey we’ve been on ever since.

GI: What does GTA III mean to Rockstar North as a development studio?

AG: GTA III set the template for how we make games. We [learned] so much from it, but mainly, we just learned how hard it was. Creating worlds with the density of detail and content we wanted that could be navigated at speed has all sorts of complications. Having the content exist in that world alongside open-world systems – the ambient world, cops, gangs, and the like, creates even more complications. I guess we learned that we weren’t afraid to take a hard path if we felt the results were worth it. And the approach of systems interacting to create complexity is something we continue to build on.

GI: This is one of those weird questions where there’s no modest way to ask it, but few people get to work on anything in their life that changes pop culture. Do you ever think about that? If so, how do you reflect?

AG: It’s an odd thing, a slightly abstract thing, really. My day-to-day life before and after GTA III has been focused on how to build the most immersive, expansive, and diverse games we can make. We always have the last game we made as the benchmark we need to push further to make something better. It’s never about how these games have been perceived culturally, critically, or commercially; it’s about what we ourselves loved about the last thing we made and how we can build on that.

From Grand Theft Auto III to Red Dead Redemption II, each of them has felt like the continuation of the same journey, and each is approached with a new sense of ambition. It’s fun and funny to see your work blow up in pop culture, to see references to it. It’s always mind-blowing to look at player stats and imagine the sheer aggregate time spent in our worlds. But beyond that, we are just incredibly grateful to get to make things we think are cool and that so many others agree enough to spend so much time with them.

This article originally appeared in Issue 341 of Game Informer.