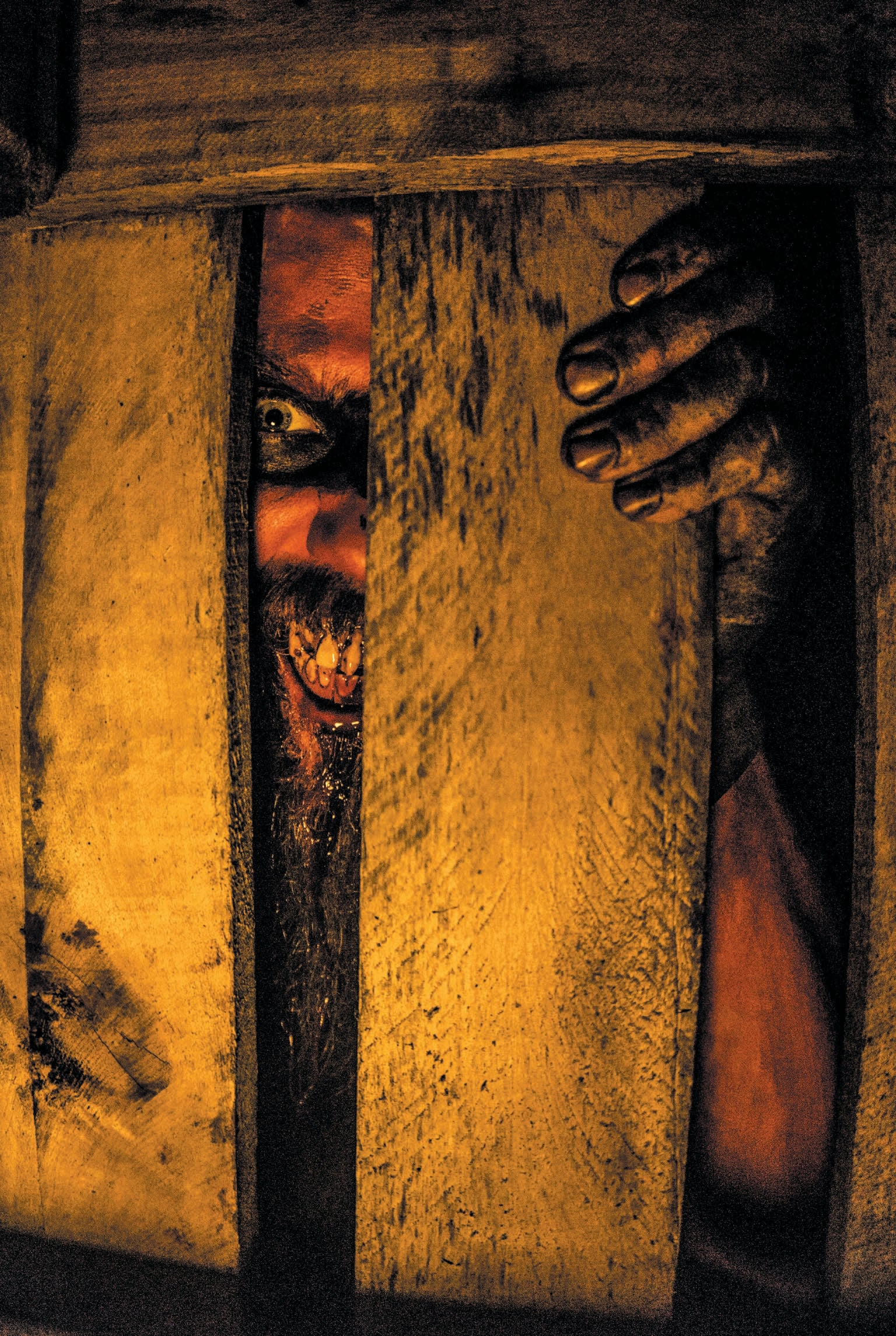

Chain saws roar, and spine-chilling screams echo from behind a dense wall of trees. You know you’re at a scary attraction in the woods of Denmark called Dystopia Haunted House, yet everything sounds so real. As you walk into the house, you become disoriented in a dark maze filled with strange objects and broken furniture; when you turn a corner, you’re confronted by bizarre scenes with evil clowns and terrifying monsters reaching out for you. Then you hear the chain saw revving up, and a masked man bursts through the wall. You scream and start running.

This might sound like the kind of place nobody would ever want to be in, but every year millions of people pay to visit haunts just like Dystopia. They crowd in during Halloween, to be sure, but show up in every other season, too. This paradox of horror’s appeal—that people want to have disturbing and upsetting experiences—has long perplexed scholars. We devour tales of psychopathic killers on true crime podcasts, watch movies about horrible monsters, play games filled with ghosts and zombies, and read books that describe apocalyptic worlds packed with our worst fears.

This paradox is now being resolved by research on the science of scary play and morbid curiosity. Our desire to experience fear, it seems, is rooted deep in our evolutionary past and can still benefit us today. Scary play, it turns out, can help us overcome fears and face new challenges—those that surface in our own lives and others that arise in the increasingly disturbing world we all live in.

The phenomenon of scary play surprised Charles Darwin. In The Descent of Man, he wrote that he had heard about captive monkeys that, despite their fear of snakes, kept lifting the lid of a box containing the reptiles to peek inside. Intrigued, Darwin turned the story into an experiment: He put a bag with a snake inside it in a cage full of monkeys at the London Zoological Gardens. A monkey would cautiously walk up to the bag, slowly open it, and peer down inside before shrieking and racing away. After seeing one monkey do this, another monkey would carefully walk over to the bag to take a peek, then scream and run. Then another would do the same thing, then another.

The monkeys were “satiating their horror,” as Darwin put it. Morbid fascination with danger is widespread in the animal kingdom—it’s called predator inspection. The inspection occurs when an animal looks at or even approaches a predator rather than simply fleeing. This behavior occurs across a range of animals, from guppies to gazelles.

At first blush, getting close to danger seems like a bad idea. Why would natural selection have instilled in animals a curiosity about the very things they should be avoiding? But there is an evolutionary logic to these actions. Morbid curiosity is a powerful way for animals to gain information about the most dangerous things in their environment. It also gives them an opportunity to practice dealing with scary experiences.

When you consider that many prey animals live close to their predators, the benefits of morbidly curious behavior such as predator inspection become clear. For example, it’s not uncommon for a gazelle to cross paths with a cheetah on the savanna. It might seem like a gazelle should always run when it sees a cheetah. Fleeing, however, is physiologically expensive; if a gazelle ran every time it saw a cheetah, it would exhaust precious calories and lose out on opportunities for other activities that are important to its survival and reproduction.

Consider the perspective of the predator, too. It may seem like a cheetah should chase after a gazelle anytime it sees one. But for a cheetah, it’s not easy to just grab a bite; hunting is an energetically costly exercise that doesn’t always end in success. As long as the cheetah isn’t starving, it should chase a prey animal only when the chances of capturing it are reasonably high.

If it’s best for gazelles to run only when the cheetah is hunting, then they benefit if they can identify when a cheetah is hungry. And the only way for a gazelle to learn about cheetahs is by closely observing them when it’s relatively safe to do so. For example, if the surrounding grass is short and a cheetah is easily visible, a gazelle feels safer and is more likely to linger a while and watch the cheetah, especially if the gazelle is among a larger group. The age of the gazelle matters, too; adolescents and young adults—those fast enough to escape and without much previous exposure to predators—are the most likely to inspect cheetahs. The trade-off makes sense: these gazelles don’t know much about dangerous cats yet, so they have a lot to gain from investigating them. Relative safety and inexperience are two of the most powerful moderators of predator inspection in animals—and of morbid curiosity in humans.

Today people inspect predators through stories and movies. Depictions of predators are found in stories passed along through oral traditions around the world. Leopards, tigers and wolves are frequent antagonists in regional folklore. We also tell stories and see films about monstrous fictional predators such as ferocious werewolves, mighty dragons, clever vampires and bloodthirsty ogres.

Indulging in stories about threats is a frighteningly effective and valuable strategy. Such tales let us learn about potential predators or menacing situations that other people have encountered without having to face them ourselves. The exaggerated perils of fictional monsters create strong emotional and behavioral responses, familiarizing us with these reactions for when we have to deal with more down-to-earth dangers.

Children are often the intended audience for scary oral stories because these stories can help them learn about risks early in their lives. Think about the key lines of Little Red Riding Hood:

“Grandmother, what big eyes you have!”

“All the better to see with, my child.”

“Grandmother, what big teeth you have got!”

“All the better to eat you up with.”

The tale teaches a young audience, in a safe and entertaining way, what wolves look like and what certain parts of a wolf do. The story takes place in the woods, where wolves are typically found. It’s scary, but told in a secure space, it delivers a valuable lesson.

Our fascination with things that can harm or kill us is not limited to predators. We also can be morbidly drawn to tales of large-scale frightening situations such as volcanic eruptions, pandemics, dangerous storms and a large variety of apocalyptic events. This is where the magic of a scary story really shines: it’s the only way to learn about and rehearse responses to dangers we have yet to face.

Most people were feeling pretty uncertain about the future in 2020. COVID had thrust the world into a global pandemic. Governments were restricting movement, businesses were closing, and the way of living that many were used to was screeching to a halt.

But some of us had seen something like it before. Less than a decade earlier meningoencephalitic virus 1, or MEV-1, was wreaking havoc. It spread with terrifying speed and without requiring close contact in subways, elevators and outdoor public spaces. Society’s response to MEV-1 foreshadowed what would happen in 2020 with COVID: travel stopped, businesses closed, and people started stockpiling supplies. Some of them began touting dubious miracle cures.

If you don’t remember the worldwide devastation of MEV-1, you must not have seen the movie Contagion, a 2011 thriller starring Matt Damon, Kate Winslet and Laurence Fishburne. Watching it might have benefited you when COVID spread across the planet. In a study that one of us (Scrivner) conducted in the early months of the pandemic, those who had seen at least one pandemic-themed movie reported feeling much more prepared for the societal surprises that COVID had in store. The stockpiling of supplies, business closures, travel bans and miracle cures were all things fans of Contagion had seen before; they had already played with the idea of a global pandemic before the real thing happened.

Learning to regain composure and adapt in the face of surprise and uncertainty seems to be a key evolutionary function of play. Engaging in play that simulates threatening situations helps juvenile mammals such as tiger cubs and wolf pups practice quickly regaining stable movement and emotional composure. Humans do this as well. Call to mind a backyard party where young children squeal with fear and delight as they are chased by a fun-loving parent who threatens, with arms outstretched in monster pose, “I’m gonna get you!” It’s all just fun and games, but it’s also a chance for the kids to try to maintain their motor control under stress so they don’t tumble to the ground, making themselves vulnerable to a predator—or a tickle attack from the parent.

Researchers who study human fun and games have argued that the decline of thrilling, unstructured play over the past few decades has contributed to a rise in childhood anxiety over that same time period. School and park playgrounds used to be arenas for this kind of play, but an increased emphasis on playground safety has removed opportunities for it. Don’t get us wrong: safety is a good thing. Many playgrounds of the past were dangerous, with ladders climbing upward of 20 feet to rusty slides with no rails. But making playgrounds too safe and sterile can have unintended consequences, including depriving children of opportunities to learn about themselves and their abilities to manage challenging and scary situations. Kids need to be able to exercise some independence, which often involves a bit of risky play.

Many scientists who study play have proposed that adventurous play can help build resilience and reduce fear in children. In line with this research, organizations such as LetGrow have created programs for schools and parents to foster independence, curiosity and exploration in children. Their solution is simple: let kids engage in more challenging, unstructured play so they can learn how to handle fear, anxiety and danger without it being too overwhelming.

Even virtual scary experiences provide many of these same benefits. The Games for Emotional and Mental Health Lab created a horror biofeedback game called MindLight that has been shown to reduce anxiety in children. The game centers on a child named Arty who finds himself at his grandmother’s house. When he goes inside, he sees that it has been enveloped in darkness and taken over by evil, shadowy creatures that can resemble everything from blobs to catlike predators. Arty must save his grandmother from the darkness and bring light back to her house. He has nothing to defend himself with except a light attached to his hat—his “mindlight.” Players controlling Arty must use the mindlight to expose and defeat the creatures.

But there’s a catch: as a player becomes more stressed (as measured by an electroencephalogram), their mindlight dims. The player must stay calm in the face of fear by practicing techniques such as replacement of stress-producing thoughts or muscle relaxation, borrowed from cognitive-behavioral therapy. As they regain their composure, their mindlight grows in power, and they are able to defeat the monsters with it. This combination of therapeutic techniques and positive reinforcement (kids defeat the monsters and conquer their fear) makes MindLight a potent antianxiety tool. Randomized clinical trials with children have shown the game to be as effective at reducing several anxiety symptoms as traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy, a widely used anxiety treatment.

Scary play can help adults navigate fear and anxiety, too. Scrivner tested this idea with visitors to Dystopia Haunted House. Haunted house goers could take personality surveys before they entered and answer questions about their experience when they exited. After about 45 minutes of being chased by zombies, monsters and a pig-man with a chain saw, the visitors ran out of the haunted house and into some members of the research team, who then asked them how they felt. A huge portion said they had learned something about themselves and believed they had some personal growth during the haunt. In particular, they reported learning the boundaries of what they can handle and how to manage their fear.

Other research from the Recreational Fear Lab in Aarhus, Denmark, has shown that people actively regulate their fear and arousal levels when engaging in scary play. This means that engaging with a frightening simulation can serve as practice for controlling arousal and may be generalizable to other, real-world stressful situations, helping people bolster their overall resilience.

In one study that supports this idea, real soldiers played a modified version of the zombie-apocalypse horror game Left 4 Dead that incorporated player arousal levels. In the game, zombies pop out of nowhere, chasing players and clawing them to the ground, generating visceral fear even in experienced video game players. In the study, some players were given visual and auditory signals when their arousal increased: a red texture partially obscured the player’s view, and they heard a heartbeat that got louder and faster as their stress increased. Later, during a live simulation of an ambush, soldiers who played the video game and received biofeedback had lower levels of cortisol (a stress biomarker) than those who did not play. Strikingly, these people also were better at giving first aid to a wounded soldier during that simulation.

These rehearsals for stress may be especially effective when people do them in groups. Collectively experiencing a dangerous situation ties people together. There are many anecdotal examples of this in history, from post-9/11 America, to military platoons, to the high levels of cooperation and assistance that often occur in the aftermath of natural disasters. There are also experimental studies showing that danger and fear can be powerful positive social forces. For example, engaging in rituals such as fire walking can physiologically synchronize people with one another and promote mutually beneficial behavior.

We don’t need exposure to real danger to reap these cooperative benefits, however. Collectively simulating upsetting or dangerous situations through scary play could confer similar benefits without the physical risk. In the health-care industry, simulations are often used to teach medical skills by creating situations that are intense. In public health, simulations have been used to teach people ways to cooperate and coordinate in pandemic preparedness and response.

In other species, learning about risks is often a social endeavor. Stickleback fish investigating predators often do so with others. One stickleback will begin approaching, then wait to see whether another will approach a little closer. Then the first stickleback will go a little further, taking its turn being the one nearest the predator. The results of studies into this behavior even suggest that sticklebacks from regions with higher predation risk are more cooperative than those from places with lower risk.

In humans, morbid curiosity seems to be associated with cooperation and risk management. For example, in many societies people tell stories about dangers in their environments, whether those are natural disasters such as fires, earthquakes and floods or threats of war, theft or exploitation from nearby groups. The Ik people of Uganda, whom one of us (Aktipis) has studied as part of the Human Generosity Project, have a collective and emotionally compelling way of engaging with concerns about raids from other groups. They enact entire plays with music, dancing and drama where they reexperience both the tragedy and the triumph of helping one another during such difficult times. Such stories and dramatic enactments can bring shared attention to these kinds of challenges, and we know that shared attention is one mechanism that can help people cooperate and solve coordination dilemmas.

A failure of group imagination, in contrast, can lead to vulnerability. Some researchers have suggested that zombie-apocalypse fiction can lead to more creative solutions during unexpected and risky events by helping people become more imaginative. With CONPLAN 8888, a fictional training scenario, the U.S. military used a hypothetical zombie apocalypse to make learning about disaster management more fun for officers. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did something similar with a comic they produced called Preparedness 101: Zombie Pandemic. Organizations have recognized that couching fears in imaginative play is productive. Right now our research team is developing a set of scary group games to help people manage shared risks and fears.

What can we learn from the human propensity for scary play? First, don’t be afraid to get out there and explore your world, even if it sometimes provokes a little fear. Second, make sure that your morbid curiosity is educating you about risks in a way that is beneficial to you. In other words, don’t get stuck doomscrolling upsetting news on the Internet; it’s a morbid-curiosity trap that, like candy, keeps you consuming but does nothing to satisfy your need for nourishment.

Instead of doomscrolling, take on one or two topics you want to know more about and do a deeper dive that leaves you feeling satisfied that you’ve assessed the risk and empowered yourself to do something about it. Be intentional about gathering more information through your own experience or by talking with others who are knowledgeable on the subject.

You can also tell or listen to scary stories with others and use them as a jumping-off point for thinking about real risks we face. Watch a movie about an apocalypse, go to a haunted house, get in costume to go on a “zombie crawl,” or have a fun night at home chatting with your friends about how you’d survive the end of the world. And finally, invite creativity and play into spaces where the gravity of a situation might otherwise be overwhelming. Make up horror stories or dress up as something frightening and have a laugh about how silly it all is. In other words, embrace the Halloween season with abandon—and then bring that same energy to the challenges of the times we’re living in now.