React has revolutionized the way we think about UI components and state

management in UI. But with every new feature request or enhancement, a

seemingly simple component can quickly evolve into a complex amalgamation

of intertwined state and UI logic.

Imagine building a simple dropdown list. Initially, it appears

straightforward – you manage the open/close state and design its

appearance. But, as your application grows and evolves, so do the

requirements for this dropdown:

- Accessibility Support: Ensuring your dropdown is usable for

everyone, including those using screen readers or other assistive

technologies, adds another layer of complexity. You need to manage focus

states,ariaattributes, and ensure your dropdown is semantically

correct. - Keyboard Navigation: Users shouldn’t be limited to mouse

interactions. They might want to navigate options using arrow keys, select

usingEnter, or close the dropdown usingEscape. This requires

additional event listeners and state management. - Async Data Considerations: As your application scales, maybe the

dropdown options aren’t hardcoded anymore. They might be fetched from an

API. This introduces the need to manage loading, error, and empty states

within the dropdown. - UI Variations and Theming: Different parts of your application

might require different styles or themes for the dropdown. Managing these

variations within the component can lead to an explosion of props and

configurations. - Extending Features: Over time, you might need additional

features like multi-select, filtering options, or integration with other

form controls. Adding these to an already complex component can be

daunting.

Each of these considerations adds layers of complexity to our dropdown

component. Mixing state, logic, and UI presentation makes it less

maintainable and limits its reusability. The more intertwined they become,

the harder it gets to make changes without unintentional side effects.

Introducing the Headless Component Pattern

Facing these challenges head-on, the Headless Component pattern offers

a way out. It emphasizes the separation of the calculation from the UI

representation, giving developers the power to build versatile,

maintainable, and reusable components.

A Headless Component is a design pattern in React where a component –

normally inplemented as React hooks – is responsible solely for logic and

state management without prescribing any specific UI (User Interface). It

provides the “brains” of the operation but leaves the “looks” to the

developer implementing it. In essence, it offers functionality without

forcing a particular visual representation.

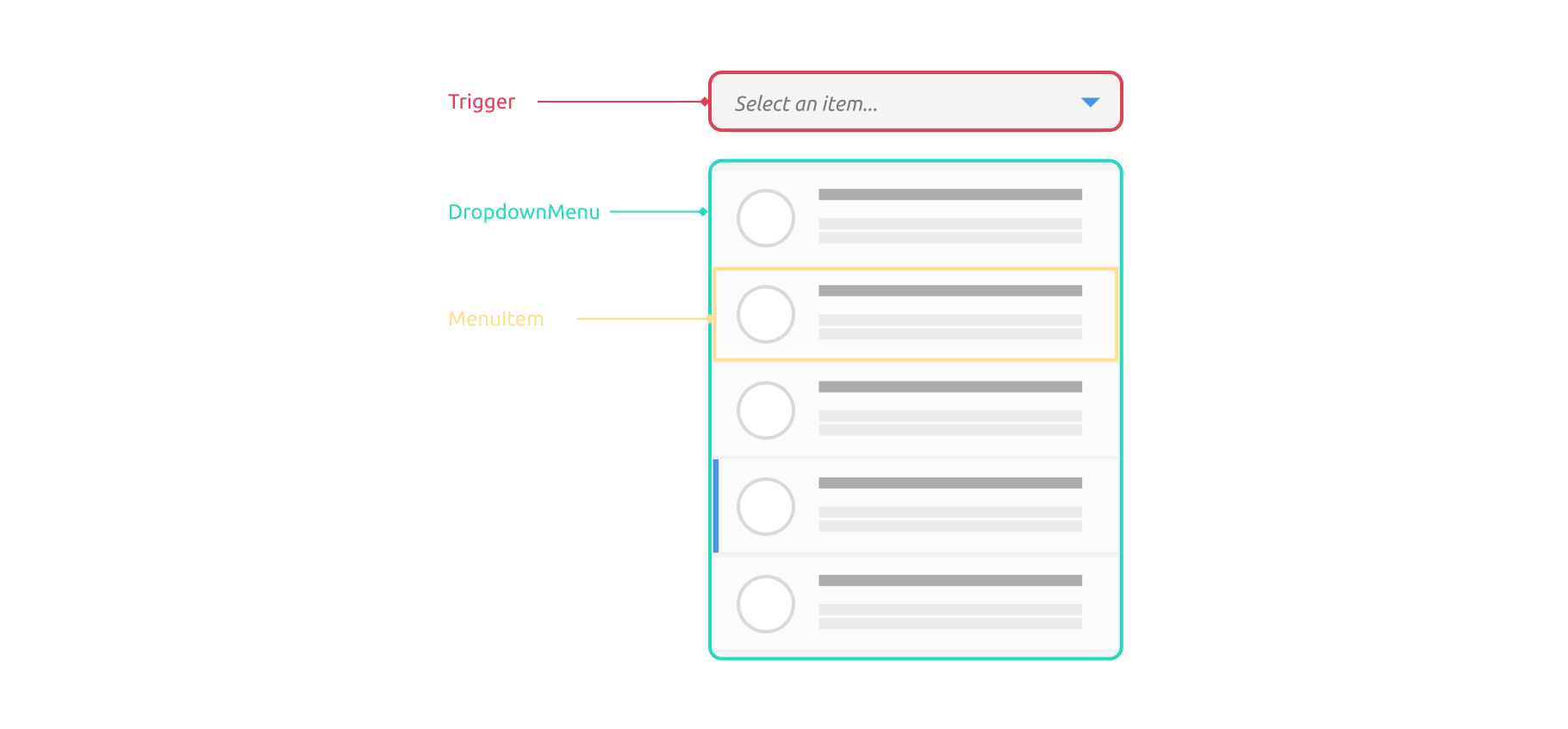

When visualized, the Headless Component appears as a slender layer

interfacing with JSX views on one side, and communicating with underlying

data models on the other when required. This pattern is particularly

beneficial for individuals seeking solely the behavior or state management

aspect of the UI, as it conveniently segregates these from the visual

representation.

Figure 1: The Headless Component pattern

For instance, consider a headless dropdown component. It would handle

state management for open/close states, item selection, keyboard

navigation, etc. When it’s time to render, instead of rendering its own

hardcoded dropdown UI, it provides this state and logic to a child

function or component, letting the developer decide how it should visually

appear.

In this article, we’ll delve into a practical example by constructing a

complex component—a dropdown list from the ground up. As we add more

features to the component, we’ll observe the challenges that arise.

Through this, we’ll demonstrate how the Headless Component pattern can

address these challenges, compartmentalize distinct concerns, and aid us

in crafting more versatile components.

Implementing a Dropdown List

A dropdown list is a common component used in many places. Although

there’s a native select component for basic use cases, a more advanced

version offering more control over each option provides a better user

experience.

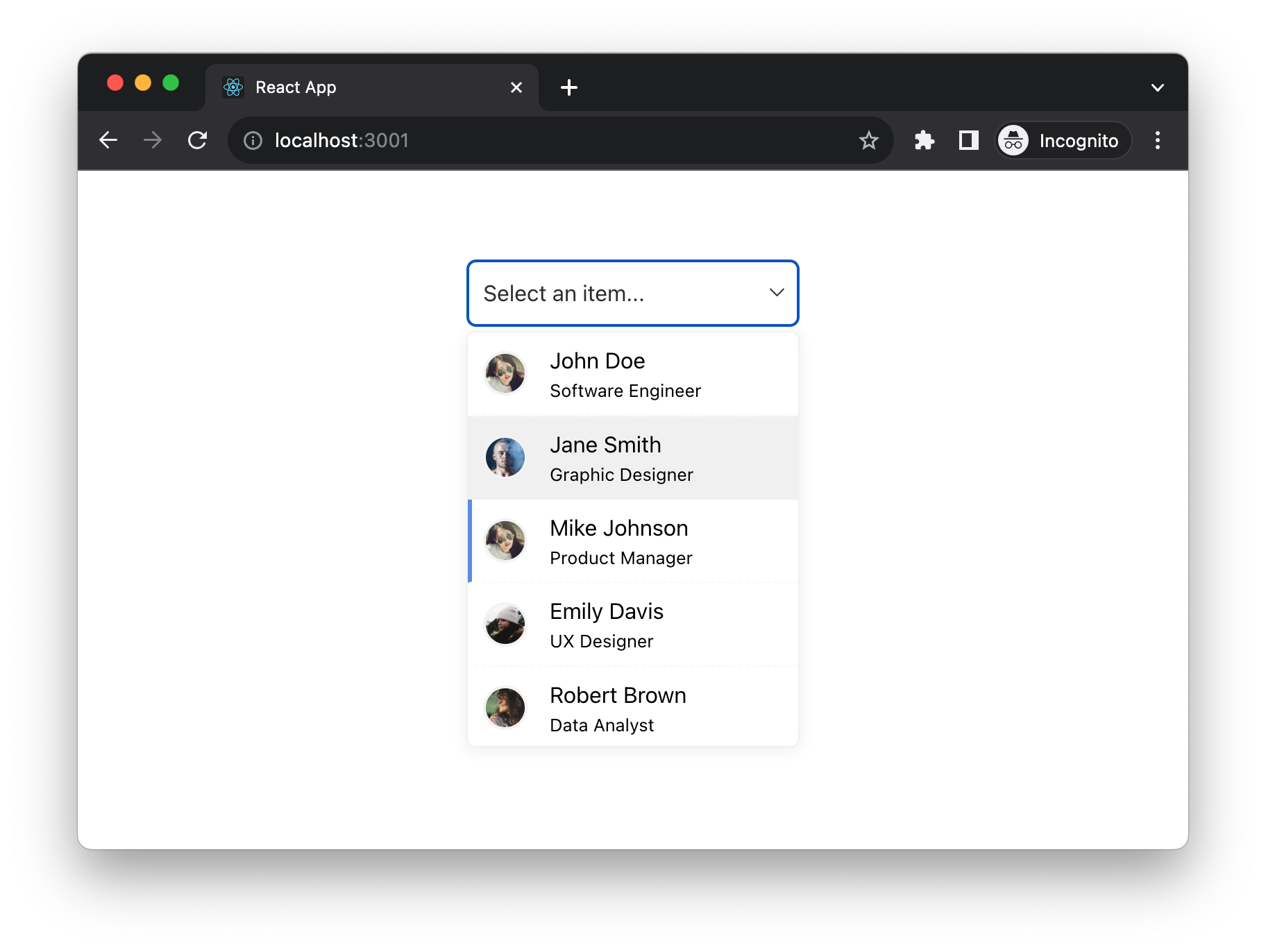

Figure 2: Dropdown list component

Creating one from scratch, a complete implementation, requires more

effort than it appears at first glance. It’s essential to consider

keyboard navigation, accessibility (for instance, screen reader

compatibility), and usability on mobile devices, among others.

We’ll begin with a simple, desktop version that only supports mouse

clicks, and gradually build in more features to make it realistic. Note

that the goal here is to reveal a few software design patterns rather

than teach how to build a dropdown list for production use – actually, I

don’t recommend doing this from scratch and would instead suggest using

more mature libraries.

Basically, we need an element (let’s call it a trigger) for the user

to click, and a state to control the show and hide actions of a list

panel. Initially, we hide the panel, and when the trigger is clicked, we

show the list panel.

import { useState } from "react";

interface Item {

icon: string;

text: string;

description: string;

}

type DropdownProps = {

items: Item[];

};

const Dropdown = ({ items }: DropdownProps) => {

const [isOpen, setIsOpen] = useState(false);

const [selectedItem, setSelectedItem] = useState<Item | null>(null);

return (

<div className="dropdown">

<div className="trigger" tabIndex={0} onClick={() => setIsOpen(!isOpen)}>

<span className="selection">

{selectedItem ? selectedItem.text : "Select an item..."}

</span>

</div>

{isOpen && (

<div className="dropdown-menu">

{items.map((item, index) => (

<div

key={index}

onClick={() => setSelectedItem(item)}

className="item-container"

>

<img src={item.icon} alt={item.text} />

<div className="details">

<div>{item.text}</div>

<small>{item.description}</small>

</div>

</div>

))}

</div>

)}

</div>

);

};

In the code above, we’ve set up the basic structure for our dropdown

component. Using the useState hook, we manage the isOpen and

selectedItem states to control the dropdown’s behavior. A simple click

on the trigger toggles the dropdown menu, while selecting an item

updates the selectedItem state.

Let’s break down the component into smaller, manageable pieces to see

it more clearly. This decomposition isn’t part of the Headless Component

pattern, but breaking a complex UI component into pieces is a valuable

activity.

We can start by extracting a Trigger component to handle user

clicks:

const Trigger = ({

label,

onClick,

}: {

label: string;

onClick: () => void;

}) => {

return (

<div className="trigger" tabIndex={0} onClick={onClick}>

<span className="selection">{label}</span>

</div>

);

};

The Trigger component is a basic clickable UI element, taking in a

label to display and an onClick handler. It remains agnostic to its

surrounding context. Similarly, we can extract a DropdownMenu

component to render the list of items:

const DropdownMenu = ({

items,

onItemClick,

}: {

items: Item[];

onItemClick: (item: Item) => void;

}) => {

return (

<div className="dropdown-menu">

{items.map((item, index) => (

<div

key={index}

onClick={() => onItemClick(item)}

className="item-container"

>

<img src={item.icon} alt={item.text} />

<div className="details">

<div>{item.text}</div>

<small>{item.description}</small>

</div>

</div>

))}

</div>

);

};

The DropdownMenu component displays a list of items, each with an

icon and a description. When an item is clicked, it triggers the

provided onItemClick function with the selected item as its

argument.

And then Within the Dropdown component, we incorporate Trigger

and DropdownMenu and supply them with the necessary state. This

approach ensures that the Trigger and DropdownMenu components remain

state-agnostic and purely react to passed props.

const Dropdown = ({ items }: DropdownProps) => {

const [isOpen, setIsOpen] = useState(false);

const [selectedItem, setSelectedItem] = useState<Item | null>(null);

return (

<div className="dropdown">

<Trigger

label={selectedItem ? selectedItem.text : "Select an item..."}

onClick={() => setIsOpen(!isOpen)}

/>

{isOpen && <DropdownMenu items={items} onItemClick={setSelectedItem} />}

</div>

);

};

In this updated code structure, we’ve separated concerns by creating

specialized components for different parts of the dropdown, making the

code more organized and easier to manage.

Figure 3: List native implementation

As depicted in the image above, you can click the “Select an item…”

trigger to open the dropdown. Selecting a value from the list updates

the displayed value and subsequently closes the dropdown menu.

At this point, our refactored code is clear-cut, with each segment

being straightforward and adaptable. Modifying or introducing a

different Trigger component would be relatively straightforward.

However, as we introduce more features and manage additional states,

will our current components hold up?

Let’s find out with a a crucial enhancement for a serious dopdown

list: keyboard navigation.

Implementing Headless Component with a Custom Hook

To address this, we’ll introduce the concept of a Headless Component

via a custom hook named useDropdown. This hook efficiently wraps up

the state and keyboard event handling logic, returning an object filled

with essential states and functions. By de-structuring this in our

Dropdown component, we keep our code neat and sustainable.

The magic lies in the useDropdown hook, our protagonist—the

Headless Component. This versatile unit houses everything a dropdown

needs: whether it’s open, the selected item, the highlighted item,

reactions to the Enter key, and so forth. The beauty is its

adaptability; you can pair it with various visual presentations—your JSX

elements.

const useDropdown = (items: Item[]) => {

// ... state variables ...

// helper function can return some aria attribute for UI

const getAriaAttributes = () => ({

role: "combobox",

"aria-expanded": isOpen,

"aria-activedescendant": selectedItem ? selectedItem.text : undefined,

});

const handleKeyDown = (e: React.KeyboardEvent) => {

// ... switch statement ...

};

const toggleDropdown = () => setIsOpen((isOpen) => !isOpen);

return {

isOpen,

toggleDropdown,

handleKeyDown,

selectedItem,

setSelectedItem,

selectedIndex,

};

};

Now, our Dropdown component is simplified, shorter and easier to

understand. It leverages the useDropdown hook to manage its state and

handle keyboard interactions, demonstrating a clear separation of

concerns and making the code easier to understand and manage.

const Dropdown = ({ items }: DropdownProps) => {

const {

isOpen,

selectedItem,

selectedIndex,

toggleDropdown,

handleKeyDown,

setSelectedItem,

} = useDropdown(items);

return (

<div className="dropdown" onKeyDown={handleKeyDown}>

<Trigger

onClick={toggleDropdown}

label={selectedItem ? selectedItem.text : "Select an item..."}

/>

{isOpen && (

<DropdownMenu

items={items}

onItemClick={setSelectedItem}

selectedIndex={selectedIndex}

/>

)}

</div>

);

};

Through these modifications, we have successfully implemented

keyboard navigation in our dropdown list, making it more accessible and

user-friendly. This example also illustrates how hooks can be utilized

to manage complex state and logic in a structured and modular manner,

paving the way for further enhancements and feature additions to our UI

components.

The beauty of this design lies in its distinct separation of logic

from presentation. By ‘logic’, we refer to the core functionalities of a

select component: the open/close state, the selected item, the

highlighted element, and the reactions to user inputs like pressing the

ArrowDown when choosing from the list. This division ensures that our

component retains its core behavior without being bound to a specific

visual representation, justifying the term “Headless Component”.

Testing the Headless Component

The logic of our component is centralized, enabling its reuse in

diverse scenarios. It’s crucial for this functionality to be reliable.

Thus, comprehensive testing becomes imperative. The good news is,

testing such behavior is straightforward.

We can evaluate state management by invoking a public method and

observing the corresponding state change. For instance, we can examine

the relationship between toggleDropdown and the isOpen state.

const items = [{ text: "Apple" }, { text: "Orange" }, { text: "Banana" }];

it("should handle dropdown open/close state", () => {

const { result } = renderHook(() => useDropdown(items));

expect(result.current.isOpen).toBe(false);

act(() => {

result.current.toggleDropdown();

});

expect(result.current.isOpen).toBe(true);

act(() => {

result.current.toggleDropdown();

});

expect(result.current.isOpen).toBe(false);

});

Keyboard navigation tests are slightly more intricate, primarily due

to the absence of a visual interface. This necessitates a more

integrated testing approach. One effective method is crafting a fake

test component to authenticate the behavior. Such tests serve a dual

purpose: they provide an instructional guide on utilizing the Headless

Component and, since they employ JSX, offer a genuine insight into user

interactions.

Consider the following test, which replaces the prior state check

with an integration test:

it("trigger to toggle", async () => {

render(<SimpleDropdown />);

const trigger = screen.getByRole("button");

expect(trigger).toBeInTheDocument();

await userEvent.click(trigger);

const list = screen.getByRole("listbox");

expect(list).toBeInTheDocument();

await userEvent.click(trigger);

expect(list).not.toBeInTheDocument();

});

The SimpleDropdown below is a fake component,

designed exclusively for testing. It also doubles as a

hands-on example for users aiming to implement the Headless

Component.

const SimpleDropdown = () => {

const {

isOpen,

toggleDropdown,

selectedIndex,

selectedItem,

updateSelectedItem,

getAriaAttributes,

dropdownRef,

} = useDropdown(items);

return (

<div

tabIndex={0}

ref={dropdownRef}

{...getAriaAttributes()}

>

<button onClick={toggleDropdown}>Select</button>

<p data-testid="selected-item">{selectedItem?.text}</p>

{isOpen && (

<ul role="listbox">

{items.map((item, index) => (

<li

key={index}

role="option"

aria-selected={index === selectedIndex}

onClick={() => updateSelectedItem(item)}

>

{item.text}

</li>

))}

</ul>

)}

</div>

);

};

The SimpleDropdown is a dummy component crafted for testing. It

uses the centralized logic of useDropdown to create a dropdown list.

When the “Select” button is clicked, the list appears or disappears.

This list contains a set of items (Apple, Orange, Banana), and users can

select any item by clicking on it. The tests above ensure that this

behavior works as intended.

With the SimpleDropdown component in place, we’re equipped to test

a more intricate yet realistic scenario.

it("select item using keyboard navigation", async () => {

render(<SimpleDropdown />);

const trigger = screen.getByRole("button");

expect(trigger).toBeInTheDocument();

await userEvent.click(trigger);

const dropdown = screen.getByRole("combobox");

dropdown.focus();

await userEvent.type(dropdown, "{arrowdown}");

await userEvent.type(dropdown, "{enter}");

await expect(screen.getByTestId("selected-item")).toHaveTextContent(

items[0].text

);

});

The test ensures that users can select items from the dropdown using

keyboard inputs. After rendering the SimpleDropdown and clicking on

its trigger button, the dropdown is focused. Subsequently, the test

simulates a keyboard arrow-down press to navigate to the first item and

an enter press to select it. The test then verifies if the selected item

displays the expected text.

While utilizing custom hooks for Headless Components is common, it’s not the sole approach.

In fact, before the advent of hooks, developers employed render props or Higher-Order

Components to implement Headless Components. Nowadays, even though Higher-Order

Components have lost some of their previous popularity, a declarative API employing

React context continues to be fairly favoured.

Declarative Headless Component with context API

I’ll showcase an alternate declarative method to attain a similar outcome,

employing the React context API in this instance. By establishing a hierarchy

within the component tree and making each component replaceable, we can offer

users a valuable interface that not only functions effectively (supporting

keyboard navigation, accessibility, etc.), but also provides the flexibility

to customize their own components.

import { HeadlessDropdown as Dropdown } from "./HeadlessDropdown";

const HeadlessDropdownUsage = ({ items }: { items: Item[] }) => {

return (

<Dropdown items={items}>

<Dropdown.Trigger as={Trigger}>Select an option</Dropdown.Trigger>

<Dropdown.List as={CustomList}>

{items.map((item, index) => (

<Dropdown.Option

index={index}

key={index}

item={item}

as={CustomListItem}

/>

))}

</Dropdown.List>

</Dropdown>

);

};

The HeadlessDropdownUsage component takes an items

prop of type array of Item and returns a Dropdown

component. Inside Dropdown, it defines a Dropdown.Trigger

to render a CustomTrigger component, a Dropdown.List

to render a CustomList component, and maps through the

items array to create a Dropdown.Option for each

item, rendering a CustomListItem component.

This structure enables a flexible, declarative way of customizing the

rendering and behavior of the dropdown menu while keeping a clear hierarchical

relationship between the components. Please observe that the components

Dropdown.Trigger, Dropdown.List, and

Dropdown.Option supply unstyled default HTML elements (button, ul,

and li respectively). They each accept an as prop, enabling users

to customize components with their own styles and behaviors.

For example, we can define these customised component and use it as above.

const CustomTrigger = ({ onClick, ...props }) => (

<button className="trigger" onClick={onClick} {...props} />

);

const CustomList = ({ ...props }) => (

<div {...props} className="dropdown-menu" />

);

const CustomListItem = ({ ...props }) => (

<div {...props} className="item-container" />

);

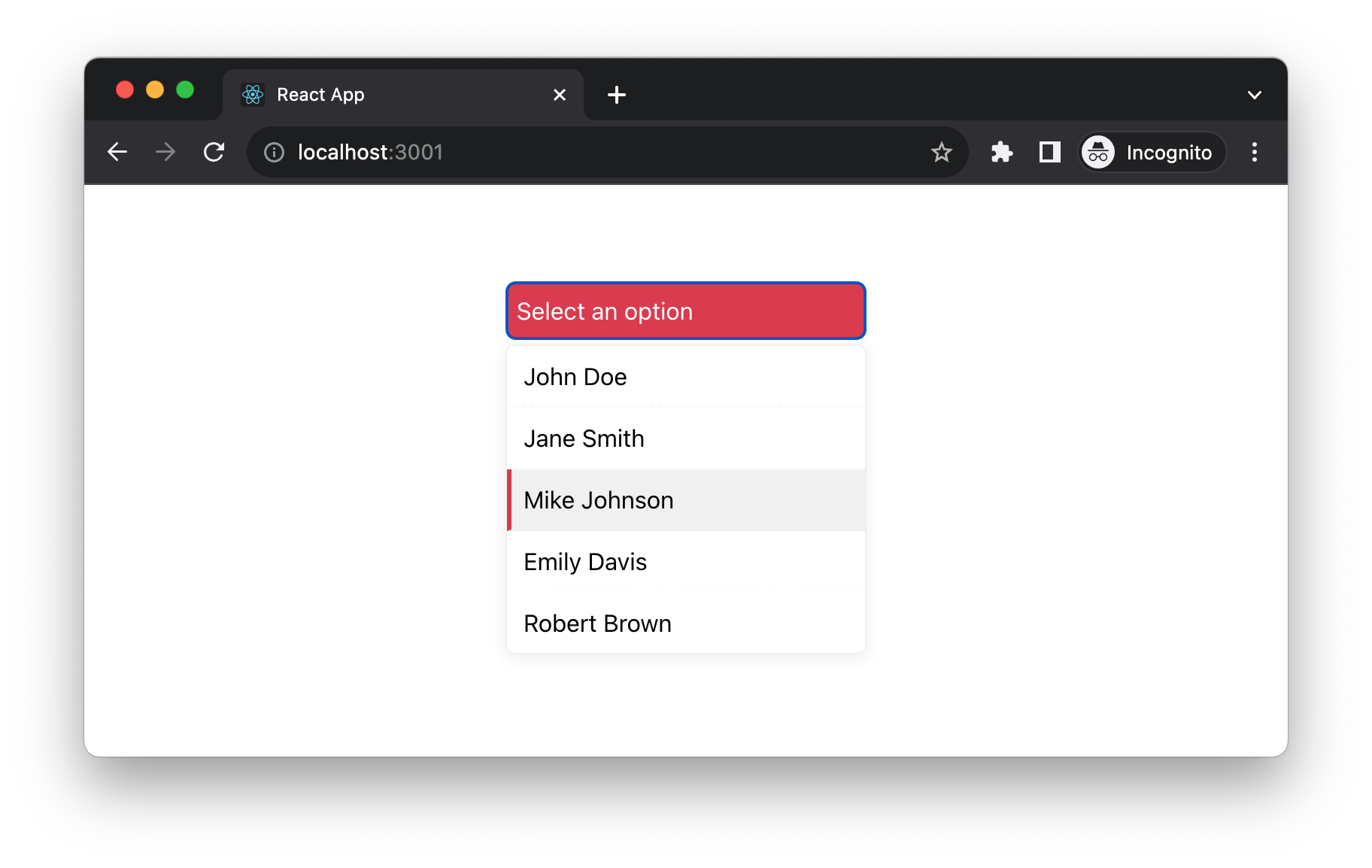

Figure 4: Declarative User Interface with customised

elements

The implementation isn’t complicated. We can simply define a context in

Dropdown (the root element) and put all the states need to be

managed inside, and use that context in the children nodes so they can access

the states (or change these states via APIs in the context).

type DropdownContextType<T> = {

isOpen: boolean;

toggleDropdown: () => void;

selectedIndex: number;

selectedItem: T | null;

updateSelectedItem: (item: T) => void;

getAriaAttributes: () => any;

dropdownRef: RefObject<HTMLElement>;

};

function createDropdownContext<T>() {

return createContext<DropdownContextType<T> | null>(null);

}

const DropdownContext = createDropdownContext();

export const useDropdownContext = () => {

const context = useContext(DropdownContext);

if (!context) {

throw new Error("Components must be used within a <Dropdown/>");

}

return context;

};

The code defines a generic DropdownContextType type, and a

createDropdownContext function to create a context with this type.

DropdownContext is created using this function.

useDropdownContext is a custom hook that accesses this context,

throwing an error if it’s used outside of a <Dropdown/>

component, ensuring proper usage within the desired component hierarchy.

Then we can define components that use the context. We can start with the

context provider:

const HeadlessDropdown = <T extends { text: string }>({

children,

items,

}: {

children: React.ReactNode;

items: T[];

}) => {

const {

//... all the states and state setters from the hook

} = useDropdown(items);

return (

<DropdownContext.Provider

value={{

isOpen,

toggleDropdown,

selectedIndex,

selectedItem,

updateSelectedItem,

}}

>

<div

ref={dropdownRef as RefObject<HTMLDivElement>}

{...getAriaAttributes()}

>

{children}

</div>

</DropdownContext.Provider>

);

};

The HeadlessDropdown component takes two props:

children and items, and utilizes a custom hook

useDropdown to manage its state and behavior. It provides a context

via DropdownContext.Provider to share state and behavior with its

descendants. Within a div, it sets a ref and applies ARIA

attributes for accessibility, then renders its children to display

the nested components, enabling a structured and customizable dropdown

functionality.

Note how we use useDropdown hook we defined in the previous

section, and then pass these values down to the children of

HeadlessDropdown. Following this, we can define the child

components:

HeadlessDropdown.Trigger = function Trigger({

as: Component = "button",

...props

}) {

const { toggleDropdown } = useDropdownContext();

return <Component tabIndex={0} onClick={toggleDropdown} {...props} />;

};

HeadlessDropdown.List = function List({

as: Component = "ul",

...props

}) {

const { isOpen } = useDropdownContext();

return isOpen ? <Component {...props} role="listbox" tabIndex={0} /> : null;

};

HeadlessDropdown.Option = function Option({

as: Component = "li",

index,

item,

...props

}) {

const { updateSelectedItem, selectedIndex } = useDropdownContext();

return (

<Component

role="option"

aria-selected={index === selectedIndex}

key={index}

onClick={() => updateSelectedItem(item)}

{...props}

>

{item.text}

</Component>

);

};

We defined a type GenericComponentType to handle a component or an

HTML tag along with any additional properties. Three functions

HeadlessDropdown.Trigger, HeadlessDropdown.List, and

HeadlessDropdown.Option are defined to render respective parts of

a dropdown menu. Each function utilizes the as prop to allow custom

rendering of a component, and spreads additional properties onto the rendered

component. They all access shared state and behavior via

useDropdownContext.

HeadlessDropdown.Triggerrenders a button by default that

toggles the dropdown menu.HeadlessDropdown.Listrenders a list container if the

dropdown is open.HeadlessDropdown.Optionrenders individual list items and

updates the selected item when clicked.

These functions collectively allow a customizable and accessible dropdown menu

structure.

It largely boils down to user preference on how they choose to utilize the

Headless Component in their codebase. Personally, I lean towards hooks as they

don’t involve any DOM (or virtual DOM) interactions; the sole bridge between

the shared state logic and UI is the ref object. On the other hand, with the

context-based implementation, a default implementation will be provided when the

user decides to not customize it.

In the upcoming example, I’ll demonstrate how effortlessly we can

transition to a different UI while retaining the core functionality with the useDropdown hook.