November 1, 2023

2 min read

From stray bullets to power companies, humans spark almost all of California’s wildfires

Flames consumed multiple homes as the Caldor Fire pushed into the Echo Summit area in California on August 30, 2021.

On a sweltering summer day in 2021, fire suddenly swept through drought-dried underbrush and leaped across treetops in California’s Sierra Nevada. A local father and son, charged with starting the 222,000-acre Caldor Fire with their target-shooting equipment, are among the thousands of humans accused of igniting nearly all the state’s forest fires since 2000. In addition to executives of utility companies, whose faulty electrical equipment has contributed to the state’s largest and deadliest wildfires, the list allegedly includes dirt bikers who remove spark arresters and couples celebrating anniversaries with sky lanterns. “It’s human recklessness in one form or another,” says Craig Thomas, founder of the nonprofit Fire Restoration Group.

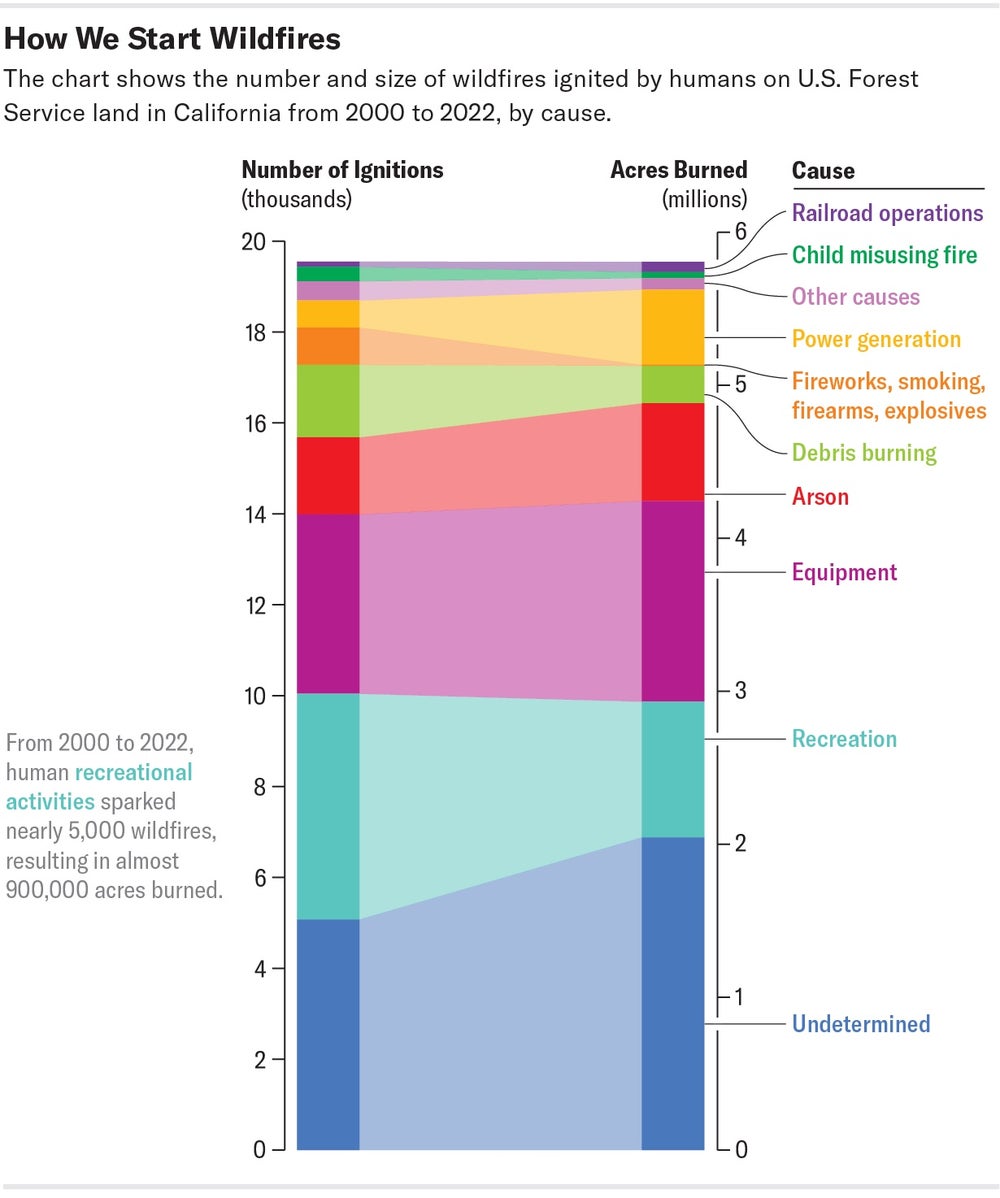

California’s forests are increasingly susceptible to wildfires because of climate change and poor forest management. As for the actual ignitions, scientists have been documenting a gradual increase in human involvement—but confronting the full extent of our responsibility remains daunting. Statewide, 95 percent of all wildfires are reportedly human-caused. Thomas, along with Brent Skaggs, a retired U.S. Forest Service forest fire management officer, used public Forest Service records to reveal an astounding 19,543 wildfires attributed to humans between 2000 and 2022 on Forest Service land in California. It’s not just campfires and cigarettes. Careless use of trucks, chain saws or other equipment starts nearly a quarter of the fires. Others are caused by illegal fireworks, as well as power generation, according to agency statistics Thomas and Skaggs analyzed for Scientific American.

Fire is a natural part of most forest ecosystems and has been around far longer than humans. For millennia, lightning sparked the vast majority of wildfires—but today it causes just 5 percent of California’s. And human-caused blazes tend to be more destructive and deadly than those caused by lightning; they often start near developed land with fewer trees and later in the season when grasses are especially combustible. California wildfires blamed on humans between 2012 and 2018 were on average 6.5 times larger than those caused by lightning strikes and killed three times as many trees. They’re also more expensive because they tend to threaten houses—more than half of wildfire-fighting costs come from defending homes.

Understanding the sources of the sparks that start the fires—not just the conditions that allow them to spread—could help save lives, homes and ecosystems, says Jennifer Balch, who studies fire ecology at University of Colorado Boulder. She emphasizes prevention in public messaging and enforcement of laws designed to reduce illegal fire starts. “We are the fire species,” Balch says. “We can do a lot to change its course on the landscape.”

With forests volatile and weather increasingly erratic, public responsibility is critical. “Don’t be doing stupid stuff in the woods,” Thomas says. “These forests can’t tolerate human recklessness.”