I’ve been a heavy user of Twitter over the last decade, and while Musk’s

purchase of Twitter hasn’t got me running for the exit, it has prompted me

to take a look at possible alternatives should Twitter change into something

no longer worthwhile for me. The obvious alternative is for me to explore

the fediverse with a

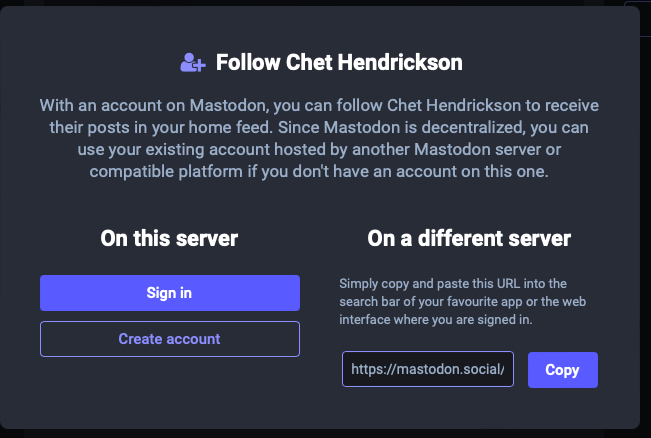

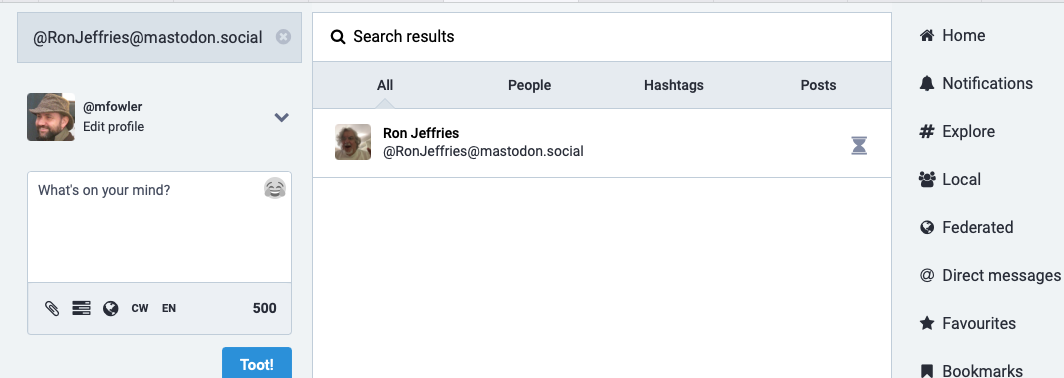

Mastodon account. As I explore using Mastodon, I’ll make some notes here so

that others can learn from my explorations.

Earlier Memos

Latest Memo: Verification on Mastodon

01 November 2022

Twitter has a facility for verifying that well-known people (for Twitter’s value of “well-known”) can have their account verified. Such accounts are shown with a blue check mark.

I got my blue check mark several years ago, and don’t remember much about it. I don’t think I asked for it, I think Twitter approached me. I don’t pay anything for it, and I don’t remember what they did to verify me. They don’t verify everyone, I suppose they did me partly due to having hundreds of thousands of followers, and partly because of being well-known in the software development world.

Due to this rather opaque way of choosing who to give out the blue check marks, Twitter verification has become somewhat fraught. It’s often seen as a status symbol. But people who don’t have it may have genuine problems with others spoofing them on Twitter.

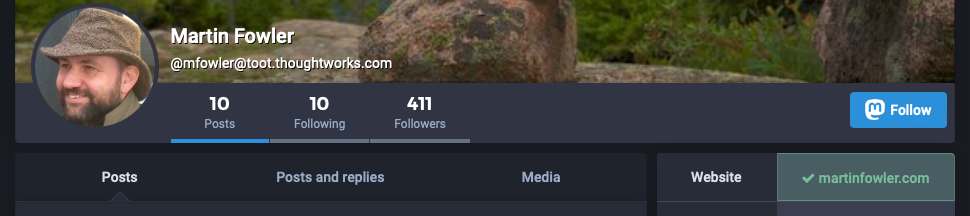

Mastodon’s approach to verification is rather different. Since it’s a decentralized system, there’s no single mechanism for verification. The way I see it, verification is up to each Mastodon instance. I’m pretty well verified on toot.thoughtworks.com because Thoughtworks is essentially verifying me by allowing me to have an account there. (As it happens, the only way to access an account at toot.thoughtworks.com is to use your corporate login.)

If Mastodon takes off, we could imagine this approach spreading widely. If a journalist at The Economist needed a verified account, then The Economist could run their own Mastodon instance, where anyone on it would be effectively verified by that newspaper. Unlike Twitter, which needs to scale to a vast amount of users, a Mastodon instance can be small enough for the organization running it to verify its members.

On the other hand, big instances like mastodon.social may not do any verification at all, because it’s just too complicated for their membership model, or they want to support anonymous accounts. That then becomes part of the choice of an instance – some folks would prefer to join an instance that can give them a viable identity.

There’s another approach to verification, which is cross-association with other parts of your web presence. On my home page I have a link to my twitter page, which is a form of verification. It indicates that the web page and the twitter account are controlled by the same user. I verify my email address in a similar way, by mentioning it on my website.

I can do this with Mastodon, of course, but can go a step further. If I include a bit of metadata on my web page, and link to that page on my Mastodon profile, then Mastodon checks for metadata, and marks my link as verified, like this:

Mastodon suggests doing this by adding this link into the body of the page

<a rel="me" href="https://toot.thoughtworks.com/@mfowler">Mastodon</a>

I did it slightly differently, adding this element to the <head> of the page

<link rel="me" href="https://toot.thoughtworks.com/@mfowler">

This mechanism allows me to tie together different bits of my online identity, helping them verify each other