I was recently in the attic of my house, going through old possessions in preparation to move across the country. Covered in dust and starting to get cranky from the effort, I found a sealed box labeled “VHS tapes.” I brought the box down to my office, grabbed a box knife, and opened it.

On top of the pile was a cassette I hadn’t thought about for years, and a rush of memories flowed back from my brain’s dim recesses.

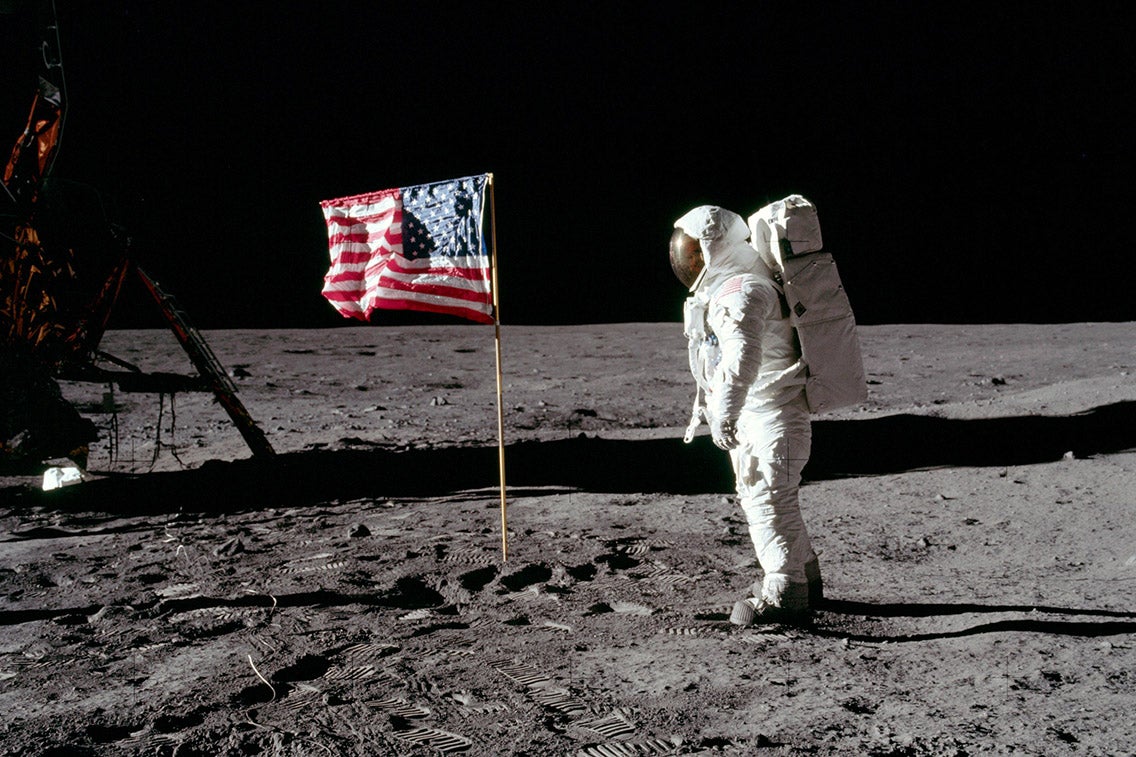

It was a professionally made copy of a television program called “Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon?” that aired in 2001. I chuckled when I saw it. I had received the tape in 2001, sent to me by my colleague Dan Vergano, who at the time wrote for USA Today (and who is now an Opinion editor here at Scientific American). He had phoned me a week earlier to ask me some astronomy questions, but as we chatted he asked if I had heard of the program, which threw doubt on the reality of the NASA Apollo moon landings, and was due to air the next week on Fox TV. I hadn’t, though coincidentally I had written a book with a chapter on people who believed the Apollo landings were faked, so he offered to send it to me.

When I got it in the mail a few days later, I watched it with equal parts disdain, disgust and frustration. The claims made were nothing new, and laughably bad. The modus operandi of this conspiracy was to lay out a claim but give only a partial explanation of it, withholding the last bit of evidence needed to truly understand it; that way, you can “just ask questions” without having to go to the effort of actually answering them satisfactorily.

I sat down and wrote an article debunking the show point by point (warning: 1990s eye-straining Web layout at that hyperlink) and waited until after the show aired to post it online. The response was overwhelming: I received hundreds of emails, some supportive, many not so much (“crackpottery” is a term I prefer). I even heard from people at NASA thanking me, including from an Apollo astronaut who, I’ll note, actually had walked on the moon.

Online traffic to my review exploded. And it’s no exaggeration to say it helped launch my career as a science communicator and antiscience debunker. I went on to give public talks all over the world based on the ridiculous claims in the show.

But this came at a cost. The TV program was extremely popular, so much so that Fox re-aired it a few weeks later. I was extremely aggravated, as a space nerd and huge Apollo fan, to see one of the greatest achievements of our technological society dishonored in such a way.

Today, though, this conspiracy theory is mostly relegated to the waste bin; you hardly hear about it anymore. People have moved on.

And that’s the problem.

Even at the time, when I gave my talks mocking the show and the conspiracy theory, I was careful to note that this type of antiscience thinking is dangerous. What if a politician—many of whom are not known for their grasp of science—were to buy into this nonsense and waste a vast amount of taxpayer money and NASA’s time investigating it?

I think about that with both a smug sense of pride at being correct and a big dollop of embarrassment for being so hugely naive. While a Congressional investigation into NASA would have been a travesty, with hindsight it would have also been a drop in a hurricane.

Since that time we’ve seen a huge rise in antivaccine nonsense. That sort of thing has been around a long time, but in 1998 Andrew Wakefield, who would go on to be a disgraced former physician, published a study in Lancet making a fraudulent link between vaccines and autism; this kicked off the modern anti-vax movement. Anti-vaxxers use many of the same sorts of bad logic and withholding of evidence as the moon hoax show did.

Around that same time creationists were making inroads into the public school system, thinly disguising their antibiology ideology as “intelligent design,” or ID. The case Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District brought this to national attention when creationists attempted to push an ID book as an alternative to a biology text in classrooms. Bad logic and withholding of needed evidence in their claims? Absolutely.

Of course even at the turn of millennium we had already been embroiled for decades in a long con played by fossil fuel industries to downplay the science of global warming as they actively encouraged the release of dozens of gigatons of carbon dioxide into our atmosphere every year. Climate science deniers make the Apollo deniers look quaint.

This list goes on. And every step of the way, these groups have been able to persuade politicians to back their views, sometimes encoding these antiscience beliefs into law. This crested in a tsunami of scientific disinformation when Donald Trump was elected president, as his attacks on reality were so numerous they became nearly impossible to keep track of. His administration’s mucking around with COVID-19, climate science, vaccinations, the EPA … all these and more had vast domestic and international repercussions, and from which the world is still reeling.

Conspiracy thinking necessarily turns the scientific process upside-down, making a conclusion first and then seeking evidence to support it, while ignoring or attacking any evidence against it. This mindset is ripe for shaping by political tribalism, which amplifies closed belief systems, inuring them from outside remediation. Cultlike behavior, such as that of the QAnon movement, may start as an outlier in such an environment but now we see it as everyday ideology from some members of Congress who were reelected in the midterms, showing that they still have support not only despite, but because of, what they believe and say. And do.

Obviously, believing that NASA faked the moon landings is not the cause of all these execrable and obviously false beliefs, but they go hand in hand. A willingness to believe claims without evidence, to dismiss expert experience, and to entertain conspiratorial ideas are all at play here, and smaller, more “fun” ideas like the Apollo hoax are a foot in the door to a universe of nonsense. They may seem harmless, but they lead nowhere good.

This is the nature of the razor-thin path of scientific reality: there’s a limited number of ways to be right, but an infinite number of ways to be wrong. Stay on it, and you see the world for what it is. Step off, and all kinds of unreality become equally plausible.

As for my Fox TV VHS tape, after a minute of reminiscing I tossed it in the trash, where it belonged.

But then, a moment later, grimacing, I retrieved it. Garbage it may be, but it’s also a symbol of what we must continue to fight, and why. It now sits on my shelf, a reminder that a single virus particle may be small, but the infection can still be toxic.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.