December 11, 2024

5 min read

A Quiet Bias Is Keeping Black Scientists from Winning Nobel Prizes

The way scientists recognize one another’s work overlooks the seminal contributions of Black scientists. The Nobel Committees need to recognize how this excludes Black scientists from awards

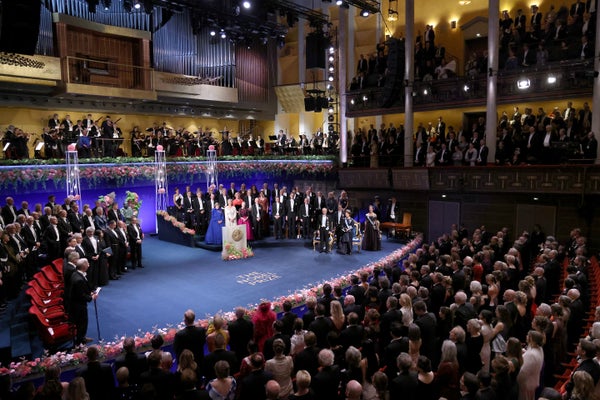

The Nobel Prize Awards Ceremony 2024 at Stockholm Concert Hall on December 10, 2024 in Stockholm, Sweden.

Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images

Marie Maynard Daly should have received a Nobel Prize. She was the first Black woman in the country to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry, and in the 1950s and 1960s she discovered the critical relationship between high cholesterol, high blood pressure and clogged arteries, and how this could cause heart attacks, strokes and other medical issues. This was a huge discovery in medicine, paving the way for the development of statins, which millions of Americans are still prescribed each year to reduce their risk of heart attack.

Such a discovery easily embodies Alfred Nobel’s legacy to award the Nobel Prizes to those who “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” And later research on cholesterol metabolism and regulation did earn several other scientists Nobels. So why didn’t Daly, who made the initial connections, win this prestigious award during her lifetime?

We think it’s because the Nobel Committees, whose selection process is notoriously secretive, place emphasis on the way scientists reference one another’s work as grounds for how important that work is. Typically, Nobel Prize–winning research is referenced more than 1,000 times before the scientists who conducted that research win. These references, known as citations, are a proxy for scientific importance but leave room for bias.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Despite their own discoveries leaning heavily on Daly’s initial findings, neither Konrad Bloch and Feodor Lynen, who won the Nobel in Physiology or Medicine in 1964, nor Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein, who won that award in 1985, mentioned her in their awards speeches. As those researchers and others made discoveries and published findings, they rarely referenced her work at all. Without such references and credit deserved, Daly and other Black scientists have not been awarded Nobels they could have rightfully earned—and instead have been suppressed, even erased, from the historical record of science.

We believe the Nobel Committees need to recognize that, whether overtly or subconsciously, scientists can and do show gender and racial bias when they recognize people as leaders in their fields. While there have been 17 Black Nobel laureates in peace, literature and economics, a Black scientist still has never won a Nobel in physiology/medicine, physics or chemistry. Asking the question “Why have Black scientists not been awarded?” is a first step toward acknowledging the contributions that Black scientists have made throughout history.

As current and future Black doctors and scientists, we are disheartened by reports that the published research of Black scientists is referenced far less often than that of their white peers. In the hierarchy of publications, the first author of a paper is typically the scientist who has done much of the experimental work it describes, while the last author is usually the scientist who has overseen the research program or the individual project—typically a very senior scientist. In studying who cites whom in neuroscience research papers, neuroscientist Maxwell A. Bertolero and others discovered that papers with white first and last authors were cited 5.4 percent more than expected, while papers with first and last authors of color were cited 9.3 percent less than expected. Inspired by this study, Fengyuan Liu, Talal Rahwan and Bedoor AlShebli, all at New York University Abu Dhabi, asked a similar question but looked deeper into four racial categories and several scientific fields. They found that Black scientists’ research is significantly undercited compared with similar research published by scientists of other races.

With such studies revealing that Black scientists’ research is often not recognized, we have been intently investigating how this difference in citation numbers could be diminishing the paradigm-shifting discoveries made by Black scientists. It is clear that the number of times a scientist’s research is referencedis important to the Nobel Committees that select each prize. The more cited you are, the more impact your work appears to have on your field. But how can this be an objective measure when citations are affected by such underlying biases? Collating all that we’ve read, it is also clear that the use of citations as a proxy for the importance of a scientific discovery unintentionally ignores the contributions of Black scientists, who are already less likely to be cited regardless of the true impact of their research. And this emphasis on citations over true impact explains scenarios such as that of Marie Maynard Daly, whose research was foundational to work that received two Nobel Prizes but whose name was not deemed worthy of such recognition. It also explains why the major scientific discoveries made by other Black scientists, such as Percy Lavon Julian, Katherine Johnson and Charles Drew, to name a few, have been overlooked by awarding bodies and the field as a whole. This is a further reflection of systemic inequities in education, mentorship, funding and recognition, all of which have been described and explored, not just in the U.S. but around the world.

Recognizing the biases in the criteria used by the Nobel Committees, and broader biases woven into academic fields when it comes to underciting Black scientists, is the first step toward creating more equal measures of scientific impact. Further addressing this underlying bias in the Nobel Committees selection process and beyond will not just help the work of Black scientists gain well-deserved recognition; it will also enrich science and society as a whole. This is not about representation; it’s about scientific innovation and progress, especially with research indicating that scientists from minority backgrounds are highly innovative.

Other prestigious award committees, such as the MacArthur Foundation, have shown that it is possible to target such biases and under-recognition; the awarding body has explicitly made a commitment to acknowledge the significant contributions of scholars of color, and the foundation has further honored a small number of Black scientists with its MacArthur Genius Grant. But scientists themselves must also play a role in correcting the historical record by ensuring that Black scientists are properly cited and receive the appropriate credit they deserve.

When the significant contributions of Black scientists are excluded, we all lose. A world without the impactful research of Daly, Julian, Johnson or Drew would look very different. This is why it is time that awarding committees and beyond finally begin acknowledging the significant discoveries made by Black scientists that benefit all of humanity—and giving them the proper recognition they deserve.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.