Nonfiction

Homage to the Bloodsuckers

A crash course in the overlooked world of parasites

Parasites: The Inside Story

by Scott L. Gardner Judy Diamond and Gabor Rácz

Illustrated by Brenda Lee

Princeton University Press, 2022 ($29.95)

Growing up on a farm in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, Scott L. Gardner would comb the rolling hills for carcasses of mice, pheasants and other expired wildlife. It was not those larger animals that intrigued the young naturalist, though, but the smaller life-forms nestled inside their organs and flesh. Gardner was after their parasites.

Gardner’s uncle, Robert L. Rausch, was a leading parasitologist with a career spanning more than 60 years. Gardner would regularly mail coiled worms, tear-shaped flukes and other specimens he found in his dissections to his uncle for identification help. One of them—a tapeworm Gardner fished out of a camas pocket gopher—turned out to be a species new to science. He later named it Hymenolepis tualatinensis, after the Tualatin River where he’d discovered it.

Gardner was hooked, so to speak. He went on to become a parasitologist at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, where he also serves as curator of the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology, one of largest parasitology collections in the world. In Parasites: The Inside Story, which Gardner co-authored with his colleagues Judy Diamond and Gabor Rácz, he shares the story of H. tualatinensis to make a larger point about parasites: these species are all around us yet woefully understudied. More and more, though, scientists are learning that parasites are facing the same survival pressures as free-living animals, including climate change, habitat loss and other anthropogenic stressors. Indeed, around his family’s farm today, the tapeworm he discovered just a few decades ago “is nowhere to be found.”

Disappearances of parasitic species such as H. tualatinensis are much more likely to go unnoticed than declines of songbirds or butterflies. Parasites are grossly overlooked by scientists and the public alike and, when acknowledged at all, are usually singled out only as agents of disease and death. Yet as the authors point out, our understanding of nature is glaringly incomplete without an understanding of parasites. These “unseen influencers” affect virtually every other species on the planet and create complex communities within every environment—communities that ultimately drive the ecology of those systems. Parasites, they assert, form “the scaffolding for all interactions among organisms.”

Parasites provides a crash course on just how ubiquitous those interactions are. The authors describe parasitoid wasps that lay their eggs inside the cocoons of other parasitoid wasps, for example, and leeches that spend their entire lives inside the anuses of hippopotamuses. Parasites also seem to have found their way to every inch of the planet, from the dry valleys of Antarctica to the highest levels of the atmosphere, where they are sometimes blown. Ecologists increasingly agree that parasites play as strong a role in shaping ecosystems as predators do.

Parasites may require up to five hosts to get from egg to larva to adult, and one of the most delightful parts of Parasites includes the 11 figures—mini comics, really—from illustrator Brenda Lee. Each one depicts a different parasite’s life cycle, from the human roundworm’s beginnings as an egg in a pile of curled feces to the prolific expulsion of tapeworm end segments from the rectum of a sperm whale that explode into millions of eggs. Outside the whale these eggs are eaten by zooplankton, where they hatch into larvae. Infected zooplankton are in turn eaten by fish that are eaten by whales, beginning the cycle all over again.

In spite of this co-dependent lifestyle, parasites can be opportunistically nimble, “switching hosts over time as possibilities for new colonization become available,” as Gardner and his colleagues write. Tapeworms, for example, survived the most recent asteroid impact that took out three quarters of all life on Earth by jumping from marine-based hosts to seabirds. Yet co-dependence can also make parasites vulnerable. If a parasitic species’ host suddenly goes extinct—or if conditions change precipitously—the parasites may disappear, too.

Parasites works best when it delves into the details of these surprising life histories and the evolution behind them. As a primer on the subject, it was a zippy read. But I would have enjoyed more firsthand narration of the authors’ experiences. Anecdotes such as Gardner’s boyhood discovery of the tapeworm H. tualatinensis are shared in the third person, which means readers are left to wonder how Gardner felt when he realized he had found a new species—and what his reaction was when it dawned on him that the species had vanished.

Gardner and his co-authors do not explain what caused the disappearance of H. tualatinensis. Most likely—as with so many other mysteries surrounding parasites—they simply do not know. They hint that it might have been the victim of “human environment mismanagement,” either switching to a new host or disappearing from the region entirely. What the authors can say for certain is that “the imminent loss of parasite diversity will forever curtail our understanding of how entire communities of organisms interact and evolve.” —Rachel Nuwer

Rachel Nuwer is a freelance journalist and author whose work has appeared in the New York Times and National Geographic.

Fair Measures

Measurements can be used to advance or exploit

Beyond Measure: The Hidden History of Measurement from Cubits to Quantum Constants

by James Vincent

W. W. Norton, 2022 ($32.50)

Scientific discoveries are often associated with dramatic insights, such as when the proverbial apple fell on Newton’s head. But journalist James Vincent, who covers science and technology for The Verge, argues that true progress is built inch by inch.

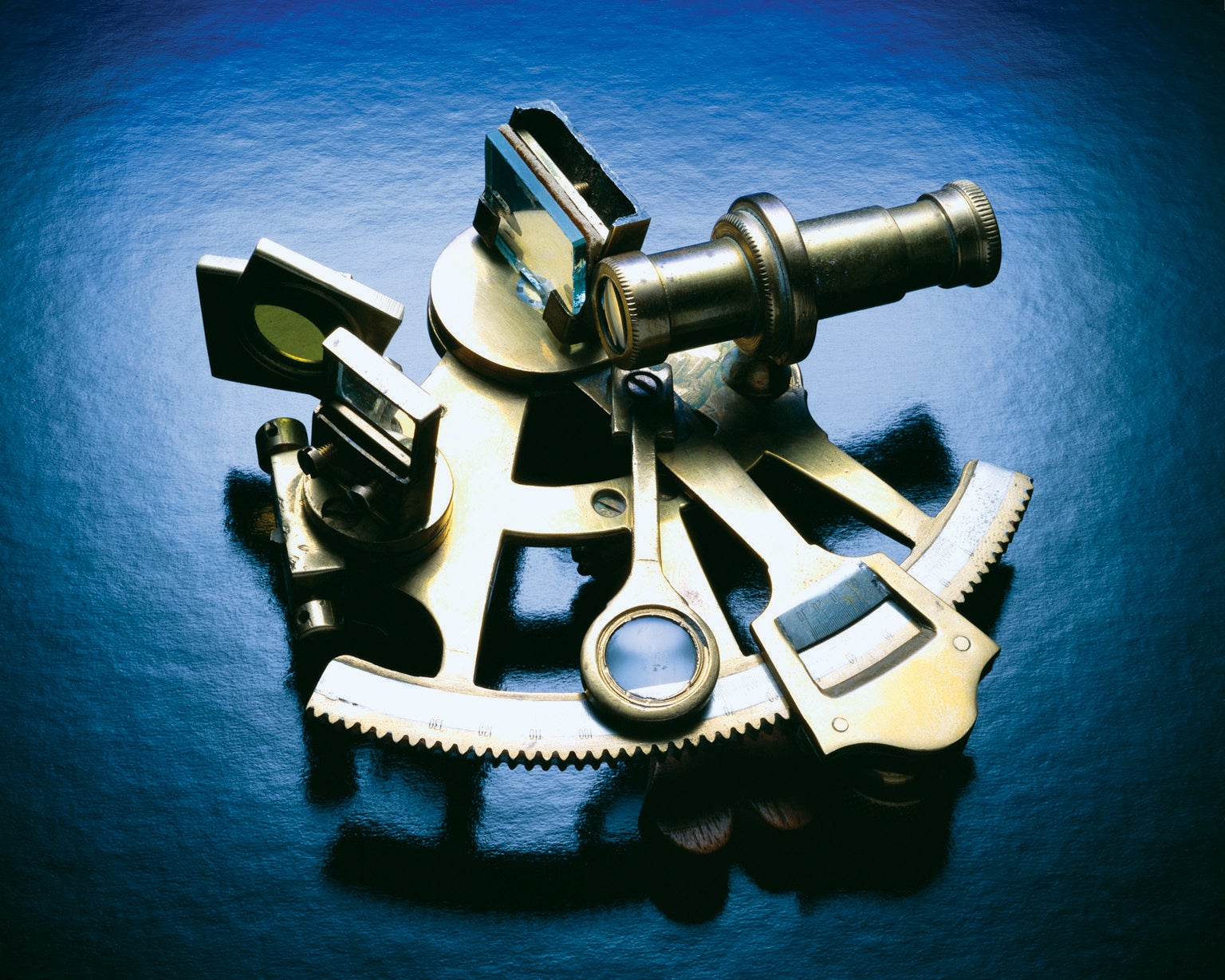

In Beyond Measure, Vincent tells the story of metrology by exploring how humanity and measurement have shaped each other throughout history. It’s an ambitious project that spans centuries, from ancient Egyptians forecasting feast or famine from the annual depth of the Nile River to the tracking and monetization of our self-measurements online by tech companies such as Google and Facebook.

Vincent masterfully draws significance out of every millimeter. He explains how informal measurements such as the pinch (as in the amount of salt used in cooking) and the cubit (the length from the elbow to the fingertip) highlight an intimate relationship between metrology and our bodies. Later he describes how the French Revolution was in part fostered by the politics surrounding the metric system.

With such a wide scope of topics—including the creation of the first thermometer, Albert A. Michelson’s experiments to determine the speed of light, and our modern reality in which human behavior is reduced to a set of statistics such as BMIs in the health-care industry—Vincent has a tendency to jump back and forth in time. This can sometimes make it hard to follow along, but it never sours the reader’s curiosity in the rich historical context he provides. The book is filled with wonder and love for a field many of us have wrongly associated with emotionless objectivity.

Beyond Measure especially shines when it portrays the innate messiness of metrology. Vincent does not just tell us that it’s difficult to find consensus on how to measure distance; he shows how the field is inextricably linked to nation building, as governments throughout history have used differing appraisals to shortchange farmers or to steal, divide and colonize Indigenous peoples’ lands. He also tackles the most sinister uses of the science, such as how statistics was exploited to support eugenics in the late 1800s. In doing so, Vincent crafts a clear-eyed and complex picture of measurement as a tool of both radical social advancement and subjugation—depending on who wields it. —Michael Welch

In Brief

In the Name of Plants: From Attenborough to Washington, the People behind Plant Names

by Sandra Knapp

University of Chicago Press, 2022 ($25)

When Shakespeare asked, “What’s in a name?” he probably wasn’t expecting as literal an answer as Sandra Knapp’s charming biographical compendium, In the Name of Plants. Some of these essays, which span both the globe and history, center on legacy figures, such as Darwin and Sequoia. Others are surprising (Lady Gaga has a fern named after her!) or strive to correct historical inaccuracies and erasures. But the book isn’t just an elegant reference text. It’s a reminder that the methods we use to classify things are inseparable from who we are. —Sara Batkie

The Creative Lives of Animals

by Carol Gigliotti

NYU Press, 2022 ($30)

From playfully bowing puppies to seductively singing alligators, Carol Gigliotti combines examples from interviews with scientists and excerpts of previously published books in this delightful index of animal inventiveness. Gigliotti explores animals’ intelligence by focusing on their creative approaches to problem-solving—how prairie dogs modify their communication to describe something they’ve never seen before, for example. Her decades spent teaching the arts to college students sparked her curiosity in the diversity of creativity, inspiring her to write a book that argues “we do not give meaning to the lives of animals; they are able and willing to do that themselves.” —Fionna M. D. Samuels

Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction

edited by Sheree Renée Thomas, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki and Zelda Knight

Tordotcom, 2022 ($27.99)

In Africa Risen, bewitching technologies and devastating magic burst forth from Africa and its diaspora in tales of once human androids crumbling in their quest to live forever, mortals scrambling to become gods, and climate disasters. This vibrant anthology—a well-paced feast of today’s most thrilling speculative fiction—has 32 short stories penned by Black authors all over the world. With settings from deserts too dry to cry in to virtual realities where anyone can rise to—or topple from—power, Africa Risen embraces darkness and struggle as readily as hope and whimsy. —Sasha Warren