Includes spoilers for The Last of Us Part I.

Even though it’s a remake of a game released in 2013 for the PlayStation 3, The Last of Us Part I is, in most respects, the same game as the original The Last of Us. Players first experiencing the game through the remake will understand the plot in much the same way. They follow the same story to the same conclusion, meeting the same characters and feeling many of the same feelings. They experience the same vision of a post-apocalyptic United States, where one traumatized man, Joel, reckons with his inability to part with his surrogate daughter, Ellie.

But despite sticking as close to the original script and general design as Part I does, it’s still, ultimately, a new game in its own right. By making a game look “better” than it did before, it’s changed into something else. Whether in small or large ways, it is altered.

In The Last of Us Part I, the most noticeable changes come by way of the character designs. Developer Naughty Dog updated the game’s visuals, improving the graphical fidelity of everything the player sees, from the stomach-churning fungus boils covering a massive “Bloater” monster to the bits of bright green grass poking out from the cracked asphalt of a ghost town’s potholed roads. It’s the cast’s faces, though, that really stick out.

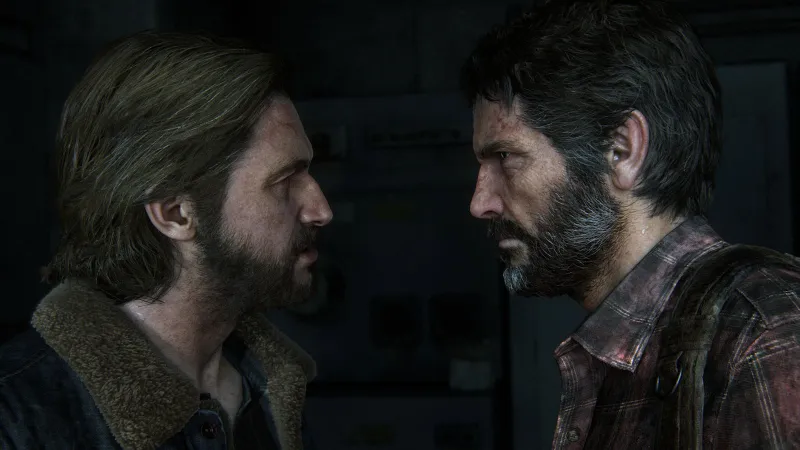

Protagonists Joel and Ellie are more naturally expressive – the elastic cartoonishness of their original faces has been replaced by realistically furrowed brows and, of course, wide-eyed expressions of horror when something tragic plays out before them. They also look pretty different as people, too. Though the change in character design is more dramatic in some cases than others, Joel, in particular, appears dramatically wearier and older than he did before. Wrinkles carve grooves in his tired face. Bruised shadows underline his eyes. The white in his hair and beard highlight his age.

He looks less soulful than before, his expressions drained of a handsome cowboy gleam and replaced with a kind of outward callousness. It makes it harder to imagine him making the sort of heroic turns that both versions of the game suggest for him, but of which he is ultimately incapable. The sense that Joel is a man running out of time – that the world has ground him down and that he has little left to cling to beyond his care for Ellie – makes it less shocking that he makes the selfish decision to stop his companion from giving her life to create a cure for a world-destroying virus. Joel has been redesigned to appear too badly beaten by the horrors of his violent life to believe in a better future.

This kind of change alters the game’s impression by subtly underscoring the original’s narrative. In other cases, the remake introduces more dramatic differences. One-off characters, from the hard-bitten residents of the Boston quarantine zone to the many human enemies Joel and Ellie kill on their journey west, now possess more detailed faces that better reflect a sense of individuality among a previously homogenous group. Instead of seeming like they’re less important than the main characters in the story, the nameless enemies give a better impression of being real, living people.

The attention paid to their faces erases some of the distinction between essential and unessential characters. As a result, their deaths feel less like the destruction of digital obstacles and more like the brutal extinguishing of human life that the original game wanted its story to communicate. This touch also brings Part I further in line with its sequel, The Last of Us Part II, which attempted to make its violence resound more strongly through touches like having enemies cry out for their friends during combat or, in a sickly feature brought into the remake, too, beg for their lives when wounded.

These visual reminders widen the scope of Part I’s world. In the original Last of Us, it was easier to abstract the dozens (or hundreds) of bandits and soldiers killed by Joel and Ellie into something other than humans. Their more personable faces help clarify the story further, showing that an entire nation lives beyond the spotlight shone on the main cast, their fates changed by bloody encounters with the protagonist – or narrowed into a seemingly eternally barbaric future when Joel chooses to save Ellie’s life rather than allow her death to provide them with a hopeful future.

While these design decisions emphasize aspects of the story already present in the original, other significant visual changes alter The Last of Us’ characters in ways that fundamentally rethink their role in the narrative.

Tess, Joel’s criminal and romantic partner from the early part of the game, has received perhaps the most dramatic redesign. The original Tess was a younger, livelier counterpart to Joel – a companion whose relative youth and similar disregard for the lives of her enemies highlighted that it wasn’t just the game’s protagonist, but also those around him who had learned to repeatedly kill others and risk their own deaths in order to eke out a living in post-apocalyptic America. Because Tess now looks as worn down and wrung out as Joel, her final moments in the story – sacrificing her life to ensure he and Ellie can escape a group of enemies in Boston – take on a different inflection.

Tess from the original game

Tess from TLOU Part I remake

Before, the younger Tess seemed representative of a future generation of post-apocalyptic people, looking for nothing more in life than companionship and the murderous work of smuggling to survive. When she gave her life for Ellie’s survival, it meant she ultimately saw the world differently from Joel when it mattered most. This decision, echoed in Ellie’s willingness to die for a cure and Joel’s final decision to condemn the world to further murder and horror because of his selfishness, meant that the original game positioned Joel as something outside of the youthful possibilities that Ellie and Tess initially represented. With Tess’ redesign, this subtle thematic touch slips away. Tess still sacrifices herself, keeping to the original script, but her doing so doesn’t carry the same thematic weight it once did.

Examples like these show that a remake is never a genuinely neutral exercise, no matter how closely it hews to the contours of the original work. This dynamic is true in the case of a bottom-up reimagining like Final Fantasy VII Remake. And it remains so in manically devotional artistic tributes like Gus Van Sant’s 1998 remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s classic, 1960 thriller Psycho, which recreated as many aspects of the original as possible, from script to shot composition. As evidence of what’s lost in even the most faithful remakes: It’s tough to find Vince Vaughn’s Norman Bates as frighteningly compelling as the original’s Anthony Perkins. Regardless of how hard a remake attempts to make something old new again without drastically tweaking its source material in the process, the very act of recreation involves new decisions that always introduce changes.

That’s because a remake – even one made by a large team like Naughty Dog – reveals the fingerprints of those who made it. Games are a product of a time and place, of the priorities of their creators at the time of creation, and, of course, of the technological affordances and constraints of their time. When Naughty Dog returned to The Last of Us for Part I, the studio did so with knowledge of the original’s successes and failures, commercially and critically. It did so with a direct sequel having been made and released. And it did so with nine years of hindsight informing its choices.

The result is that Part I, despite its many similarities, is a different game from the original Last of Us. Its characters are not the exact same characters as before, its world is not the exact same world as before, and the experience of playing it is different enough that it becomes a new work – one that might best be viewed as a different draft of the same novel, or a new cut of the same film. By recognizing those differences, both the 2013 Last of Us and The Last of Us Part I end up looking like more than just an older and newer version of the same story.

This article originally appeared in Issue 351 of Game Informer.