In one way or another, Thomas Gooch has spent more than 30 years struggling with illegal drugs. The 52-year-old Nashville, Tenn., native grew up in extreme poverty. He was first incarcerated in 1988 and spent the next 15 years in and out of jail for using and selling narcotics. “Until 2003,” Gooch says. “That was the first time I went to treatment and the last time I used.” Since then, for most of 19 years, Gooch has been trying to get others into recovery or just keep them alive. He handed out clean needles and injection-drug equipment—which reduce injuries, infections and overdose deaths—in Nashville’s hardest-hit communities. In 2014 he founded My Father’s House, a transitional recovery facility for fathers struggling with substance use disorder.

But despite Gooch’s long experience, the opioid epidemic recently has brought a level of devastation to the Black community that has shocked him. “I had never seen death the way I’ve seen death when it comes to opioid addiction,” he says. “There’s been so many funerals, it doesn’t even make sense. I personally know at least 50 to 60 individuals who died from overdoses in the last 10 years.” That staggering body count includes Gooch’s recently estranged wife in 2020 and a former partner in 2019.

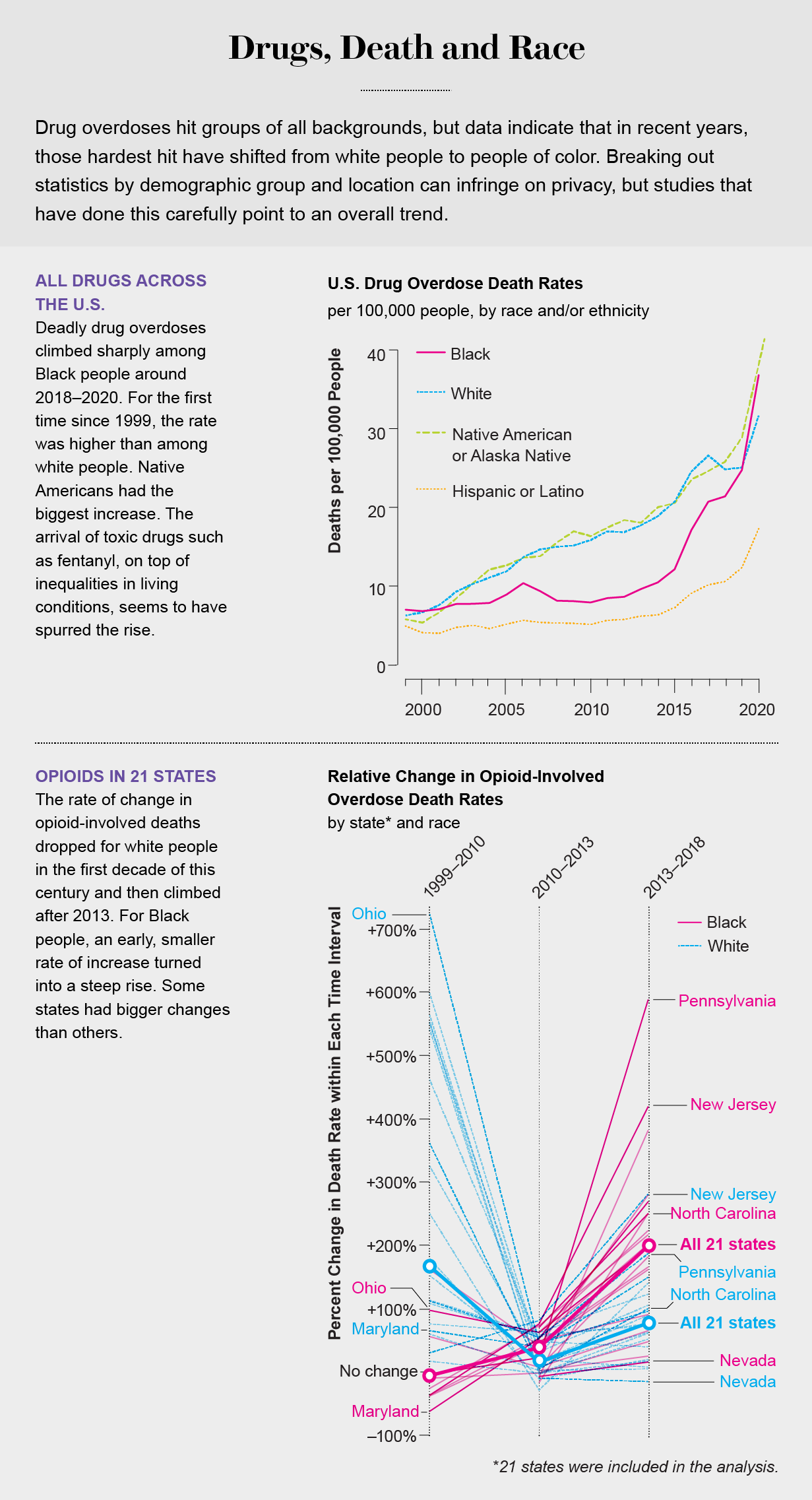

A million people in the U.S. have died of opioid overdoses since the 1990s. But the face—and race—of the opioid epidemic has changed in the past decade. Originally white and middle class, victims are now Black and brown people struggling with long-term addictions and too few resources. During 10 brutal years, opioid and stimulant deaths have increased 575 percent among Black Americans. In 2019 the overall drug overdose death rate among Black people exceeded that of whites for the first time: 36.8 versus 31.6 per 100,000. And with the addition of fentanyl, the synthetic opioid that’s 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine, Black men older than 55 who survived for decades with a heroin addiction are dying at rates four times greater than people of other races in that age group.

The reasons for this dramatic change come down to racial inequities. Research shows that Black people have a harder time getting into treatment programs than white people do, and Black people are less likely to be prescribed the gold standard medications for substance use therapy. “If you are a Black person and have an opioid use disorder, you are likely to receive treatment five years later than if you’re a white person,” says Nora D. Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health. “Treatments are extraordinarily useful in terms of preventing overdose death so you can actually recover. Five years can make the difference between being alive or not.” Black people with substance use problems are afraid of being caught up in a punitive criminal justice system and are less likely to have insurance good enough to allow them to seek help on their own. And the COVID pandemic disrupted many recovery and harm-reduction services, particularly for people of color.

Gooch blames straight-out racial discrimination in the health-care system, too. “When we call different places to try to get people into treatment, the question they ask is ‘What drug do they use?’” he recounts with exasperation. “If you say ‘crack,’ all of a sudden they ain’t got no bed available. If you say opioids and heroin, they will find a bed because that’s the demographic they want. A couple of times I told patients that the only way they’re going to get help is to get drunk and turn themselves into Vanderbilt Hospital because Vanderbilt will hold them for five days, and that’ll get them into treatment.”

Gooch is one of the people trying to improve access to therapies for addiction and change the overall dysfunctional dynamic. Other groups are bringing more effective addiction treatments within prison walls, reducing the chances of recidivism on release. A proposed federal law would make therapy with the commonly used addiction medication methadone less onerous for an impoverished population, as well as less stigmatizing. And Volkow is using her platform at the NIH to highlight the overwhelming research-based evidence for better ways to understand and treat addiction.

Access to Treatment

The nation’s historic reluctance to treat addiction as a health-care issue rather than a criminal justice one has resulted in a health-care system where too few people of any race—just 10 percent—receive treatment for substance use disorder. Several factors, such as stigma and an inability to afford or access care, make the numbers considerably more dismal among people of color. Even after a nonfatal overdose, Black patients are half as likely to be referred to or access treatment as non-Hispanic white patients, according to federal government data.

A growing recognition that criminalization and incarceration do little to curb illegal drug use or improve public health or safety has led to harm-reduction policies such as Good Samaritan laws—statutes that provide limited immunity for low-level drug violations and increase availability of naloxone, a drug that can reverse overdose. But racial disparities have emerged in the application and effectiveness of both measures. A study from RTI International found that Black and Latino intravenous drug users have inequitable access to the medication.

Loftin Wilson, program manager for the NC Harm Reduction Coalition in Durham, N.C., who has worked in the field for more than a decade, says the problems with inequality lead to distrust in the system, which creates a vicious cycle in which people who need help won’t go to institutions that can provide help. People entering treatment worry, with good reason, that dealing with the social service system can cause them to lose their employment, housing or even custody of their children. “That’s another example of the negative experiences people who use drugs have. They definitely don’t land equally on everybody, and people don’t experience them all the same way. It is a vastly different experience to be a Black drug user seeking health care than for a white person,” Wilson says.

University of Cincinnati psychologist Kathleen Burlew notes, as Volkow does, that when Black patients enter treatment, they are more likely to do so later than white people and are less likely to complete it. In addition to mistrust, she says, the less favorable outcomes result from factors such as clinician bias and lack of racial and ethnic diversity among treatment providers.

Federal resources, such as grants to support local opioid use disorder clinics and programs, also tend to favor white populations. According to 2021 data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 77 percent of the clients treated with grant funding were white, 12.9 percent were Black and 2.8 percent were Native American. The disparity is even more pronounced in some states. For example, in 2019 North Carolina announced that white people made up 88 percent of those served by its $54-million federal grant, compared with 7.5 percent for Black people. Native Americans accounted for less than 1 percent of those served.

Medication Inequality

Research has shown that there is a bias among health-care providers against using medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which combines FDA-approved drugs with counseling and behavioral therapies. Substance use specialists consider it the best approach to the opioid use problem. Yet a study published in JAMA Network found that about 40 percent of the 368 U.S. residential drug programs surveyed did not offer MAT, and 21 percent actively discouraged people from using it. Many addiction treatment programs are faith-based and see addiction as a moral problem, which leads to the conclusion that relying on medication for abstinence or sobriety simply trades one form of addiction for another. Many general practitioners who lack training in addiction medicine have this misconception.

The three medications approved by the FDA are buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone. Buprenorphine and methadone are synthetic opioids that block brain opioid receptors and reduce both cravings and withdrawal. Naltrexone is a postdetox monthly injectable that blocks the effects of opioids. Very few insurance providers in the U.S. cover all three medications, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the full range of medications is far less available to Black people.

Research suggests that economics and race influence who receives which medications. Buprenorphine, for instance, is more widely available in counties with predominantly white communities, whereas methadone clinics are usually located in poor communities of color.

To use methadone, patients must make daily visits to a clinic to receive and take the medication under the supervision of a practitioner. This requirement makes it difficult to do things that build a normal life, such as attending school and obtaining and maintaining a job. There is also the stigma of standing in a public line known to everyone passing by as a queue for addiction treatment. “The treatment model was developed [during the Nixon administration] based on racism and a stigmatized view of people with addiction without any thought of privacy or dignity or treating addiction like a health problem,” says Andrew Kolodny, medical director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University. The stigma is made worse by methadone’s classification as a Schedule II controlled substance, which is defined as a substance with a high potential for abuse, potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. This categorization pushed the medication into a quasicriminalized status and the clinics into minority communities.

Buprenorphine, however, is a completely different story. When opioid use problems increased in white communities, Congress acted to create less stigmatizing treatment options. The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (“DATA 2000”) lifted an 86-year ban that prevented treating opioid addiction with narcotic medications such as buprenorphine, which today is sold under the brand names Subutex and Suboxone. The majority of doctors who got special federal licenses to prescribe it accept only commercial health insurance and cash, so the drug is usually offered to a more affluent population, which in the U.S. means white people. About 95 percent of buprenorphine patients are white, and 34 percent have private insurance, according to a national study of data through 2015.

John Woodyear is an addiction treatment specialist in Troy, a small rural town in south central North Carolina where the epidemic is exacting an increasingly heavy toll on the Black and Native American populations. Overall overdose death rates increased 40 percent from 2019 to 2020, but death rates among those two groups in particular went up 66 and 93 percent, respectively. Yet Woodyear, who is Black and practices in a town that is 31 percent Black, says his patients are 90 percent white. People come to the clinic through word of mouth or referrals from friends. As long as Woodyear’s patients are mostly white, new patients will be mostly white as well, he says.

One exception to this racial pattern is Edwin Chapman’s clinic in the Northeast neighborhood of Washington, D.C., one of the district’s predominantly Black and most impoverished communities. Chapman, a physician, often prescribes buprenorphine to his patients with opioid use problems, and the overwhelming majority of them are Black. He says that to prescribe the drug, physicians like him must get past certain roadblocks. “The insurance companies in many states put more restrictions on patients in an urban setting, such as requiring prior authorization for addiction treatment,” he says. Further, “to increase the dose above 16 or 24 milligrams, you may have to get a prior authorization. The dosing standards were based on the white population and people who were addicted to pills. Our surviving Black population often needs a higher dose of buprenorphine.”

Chapman says few physicians in private practice are willing to treat these patients. “They don’t really feel comfortable having these patients in their office, or they aren’t really prepared to deal with the economic and mental health issues that come with this population,” he explains; those disorders include bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, among others.

People have their own biases that keep them away from medication such as buprenorphine, Wilson says. Many view it as simply trading one drug for another. “They think, ‘If I’m going to take this step, why not just go to detox and not take any medications at all?’” he says. “There’s a big cultural misunderstanding about the fact that [these] medications are the only evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder. Short-term detox isn’t the most appropriate intervention for most people.”

Gooch agrees that the bias is real. He facilitates recovery groups at a program operated by a group from Meharry Medical College, a historically Black institution. Yet “I haven’t seen one Black person yet,” Gooch says. “Some think it’s a setup. There’s so much distrust, they have a hard time thinking it’s legal. It’s just the culture of Black people. Many are religious and think [taking the drug] is wrong.”

“Those [misconceptions] are holdovers from our having been miseducated from the outset,” Chapman says. “Whites have done a tremendous job educating their community that this is a medical problem, a disease. In the African American community, drug addiction has always been and continues to be seen as a moral problem, and incarceration was the treatment.”

Hope for Change

In the November 2021 issue of Neuropsychopharmacology, Volkow argued that it is long past time for a new approach to drug addiction that would address these misconceptions within the most affected populations and biases among providers. “We have known for decades that addiction is a medical condition—a treatable brain disorder—not a character flaw or a form of social deviance,” she wrote.

Volkow argues that treatment reform should start with prison and the criminal justice system. Even though there is no difference along racial lines in who uses illegal drugs, Black people nonetheless were arrested for drug offenses at five times the rate of white people in 2016. The racial disproportionality in incarcerated drug offenders does not reflect higher rates of drug law violations, only higher rates of arrest among racial and ethnic minorities. Currently the number of arrests for heroin (which more Black people use) exceeds the arrests for diverted prescription opioids (which more white people use), even though the latter is more prevalent.

These unequal arrests and incarcerations add to the racial inequalities in drug treatment and survival rates. An estimated two thirds of people in U.S. correctional settings have a diagnosable substance use disorder, and approximately 95 percent will relapse after their release. In the two weeks postrelease, the risk of overdose increases more than 100-fold, and the chances of death increase 12-fold.

Paradoxically, that makes prisons and jails—institutions with the most obvious and overt racial disparities—the places with the greatest potential to bring about effective change. Volkow points to a recent NIH study as proof that starting substance disorder treatment during incarceration lowers the risk of probation violations and reincarcerations and improves the chances of recovery. But only one in 13 prisoners with substance use problems receives treatment, according to a Pew data analysis.

Some local programs have started to tackle some of these issues. In Pittsburgh, the Allegheny Health Network’s RIvER (Rethinking Incarceration and Empowering Recovery) Clinic opened in May 2021. Its goal is to reduce recidivism among people with addictions by providing care for the formerly incarcerated immediately on their release from jail, regardless of their ability to pay. Since opening, the clinic’s caregivers have engaged with hundreds of people.

New York City recently became the first municipality in the country to sanction overdose prevention centers where people with substance use disorder can use drugs under medical supervision. Two sites, one in East Harlem and the other in Washington Heights, opened in December 2021. They have had more than 10,000 visits and prevented nearly 200 overdoses by administering the medication naloxone.

There are other signs of change, too. California signed a law that requires every treatment provider in the state to provide a “client bill of rights” to notify patients of all aspects of recommended treatment, including no treatment at all, treatment risks and expected results. And federal authorities loosened methadone regulations during the pandemic. Instead of daily in-person visits, more patients were allowed to use telehealth consultations and take doses home. Senators Ed Markey of Massachusetts and Rand Paul of Kentucky have introduced a bill that would make that change permanent. Among other programs and initiatives across the country, these are an indication that drug treatment policy may be headed in a more equitable, evidence-based direction.