Splinter Cell’s star has faded. In the years since Sam Fisher’s last outing, 2013’s Splinter Cell: Blacklist, he’s made a handful of cameo appearances and even shown his battle-worn visage at a conference or two. And there is a remake on the way – of which we’ve only seen concept art. But by most measures, the franchise has been dormant for a decade.

Nonetheless, Fisher was once the lead of a game momentous enough to compete for sales with Halo, have Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid team taking notes, and find itself referenced as the graphical and technical benchmark of the early Xbox years. With two decades of distance, it’s hard to see the defacto mascot of novelist Tom Clancy’s video game offshoot brand as anything other than the embodiment of its ethos; the avatar of Clancy’s own stable of globe-trotting, no-nonsense, flag-waving heroes. But in fact, his wry, ironic wit and detached sarcasm point to more than just the tropes informing his character – they betray the fact that his creators couldn’t be further from Clancy’s type.

“One time I was having lunch with the guys from PAX,” says Ed Byrne, lead level designer, “and they were big fans of Splinter Cell. And when I told them this story, they were like, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, Splinter Cell was ironic? It was an ironic Clancy game?’”

Byrne recounted his memory of J.T. Petty, who wrote the script: “He was a sandal-wearing, vegan, NYU student.” Not at all the kind of guy who would keep a shelf of Jack Reacher novels.

“It was almost to the point where we just threw in all of these tropes to see what we could get away with,” Byrne said, “and every time we added more tropes, the more Clancy-like it became.”

Had Clancy shown any interest in the project, he may have objected, but Ubisoft Montreal’s work was in his periphery at best.

That a studio like Ubisoft Montreal circa 2002, still largely unproven outside of its work on licensed, kid-friendly games, could make a standout title in a genre it had never worked with, using a license much of the staff didn’t care for, with a team made up mostly of completely inexperienced developers is remarkable. That it helped cement a burgeoning genre and remained one of the top-selling Xbox titles for the console’s life is even more so.

“Seen from the inside, every game is a miracle,” writes creative lead Francois Coulon in an email interview. “Here, the planets [were] perfectly aligned.”

The story of Splinter Cell contains many such alignments, not the least of which is the unlikely pairing of, as Byrne recalls laughingly, “a bunch of bleeding heart liberals” and Clancy. Like any sufficiently complex video game, the seeds of its creation sprouted first in several different places. They came together only incidentally, through decisions and events happening separately and without connection. In the mind of a French artist dreaming up a world of floating islands, in a Paris boardroom over a game of Metal Gear Solid, in the offices of a North Carolinian animation tool company taking its first steps into a new medium.

Getting The Crew Together

Getting The Crew Together

For Nathan Wolff, it started in 1998 when he was looking for any job to get him out of his small hometown in rural Maine and into the big city: New York, New York.

“I don’t remember where. I mean, back then, it must have been in some print newspaper or something. I saw an ad for ‘video game designer.’ […] I don’t know what moment of youthful confidence I had,” Wolff says. Despite no real foreknowledge about what the job might entail, he sent a cover letter. After an unconventional interview where Wolff had to invent and flesh out game scenarios on the fly, he was hired just like that. In a couple more years, he would find himself as the lead game designer on Splinter Cell.

“Looking back, it was totally insane,” Wolff says. “I had no experience.”

He wasn’t alone, either.

Splinter Cell

“I was a new game designer, just fresh out of college,” says Ed Byrne, lead level designer. “It was all of our first gigs […] Even the senior people on the team, myself included, were first-timers.”

Whether Ubisoft intended to fill the ranks of a new studio with cheap labor by hiring green or foster innovation by bringing in untrained talent is difficult to determine. But the effect was the same either way. The small team that began work at Ubisoft New York was composed of mostly blank canvases. At first, it worked on licensed, child-friendly fare like Tarzan: Untamed. It wasn’t too dissimilar to the slightly older Ubisoft Montreal just to the north, creating titles like Tonic Trouble and Laura’s Happy Adventures – safe bets in the heyday of the licensed game era. Soon, however, an ambitious and promising project would arrive in their small, Midtown Manhattan office all the way from Paris.

The Drift

The Drift

Earlier that year, Francois Coulon, eventual associate producer and creative director of Splinter Cell, was heading up a team in Paris to develop Ubisoft’s first shooter. Upper management hadn’t shown much interest in the genre before, but Coulon convinced Ubisoft co-founder Yves Guillemot to give it a chance after showing him some scenes from Metal Gear Solid. It did the trick; the idea was greenlit with a small crew.

In early 1999, Gerard Guillemot sent Coulon’s team to New York. It brought the beginnings of its new game, The Drift.

“In a sea of kid-friendly games, The Drift was the more mature sci-fi project that caught my attention immediately,” writes lead character artist Martin Caya in an email interview.

In it, Earth had burst apart, the remains of civilization built atop the floating vestiges suspended high in the sky. Populating giant airborne islands were retro-futuristic buildings, flying cars, clunky analog gadgets, and dynamically reactive crowds. The game’s protagonist wielded a hefty gun with an attached TV monitor, a manually winding winch grapple, and an old-school switchboard used to control its main feature: a video feed to take advantage of various vision augmentations and remote projectile cameras.

Dynamic, emergent, stylish – The Drift was supposed to be it all.

Splinter Cell

“The idea was that we could probably just pick the best gameplay mechanics and combine them into a game, and that would be The Drift,” Byrne says. “But, of course, the problem is that you can’t really just combine a whole bunch of gameplay mechanics and have it be cohesive. And I think, ultimately, that’s what killed the project.”

The Drift was too ambitious for the inexperienced team at Ubisoft New York. When Ubisoft’s number crunchers looked at the cost of maintaining a small studio in downtown Manhattan, some of the nation’s most expensive real estate, the studio itself seemed a little too ambitious. The crew was offered the chance to relocate to Montreal and join the now 300-strong studio to its north. When it did, The Drift came too. It didn’t last long. Corporate told Coulon that a new IP was too risky. Now with full access to Ubisoft Montreal’s greater pool of resources and the company’s catalog of characters to choose from, Coulon was asked to retool The Drift into a pre-existing franchise. Ubisoft, of course, had no shooters to work with.

“At the time, all you could throw was Rayman’s fist!” says Coulon.

Without a character or property to guide production, the core team continued work on a generic third-person shooter, hoping something would eventually come along which might align with the work already completed.

“The head of Montreal Studio, willing to see this go into production, was coming to me every month or so with weird IP suggestions such as Pamela Anderson’s V.I.P.,” writes Coulon. The team even toyed with the idea of using James Bond. According to a 2014 article by IGN, a demo was created and used as a “shot in the dark attempt to impress the license holder,” but nothing came of it.

“And then, of course, when [Ubisoft] bought Red Storm and got the Tom Clancy license, everything changed,” says Byrne.

The Metal Gear Solid 2 Killer

The Metal Gear Solid 2 Killer

A few years earlier, Clancy had enlisted the help of Cary, North Carolina-based Virtus Corporation, an animation company with a small video game division, to adapt his novel SSN into a video game. One day after its release, the new collaborators formed Red Storm Entertainment and went on to release a handful of Clancy titles that more or less came and went before Rainbow Six rocketed the studio into the mainstream. In the summer of 2000, Ubisoft scooped up the company to acquire the Clancy license.

“I immediately called the legal head of Ubisoft in Paris,” writes Coulon. He knew what to do with the untitled, rudderless third-person shooter floating in limbo at Ubisoft Montreal. Already a fan of Clancy, Coulon saw the potential for not just a good game but one with mass market appeal. “I had my small core team read the books, see the movies, and study what the Clancy license meant.”

“They were just so awful,” says Byrne. “I can admit it now. I’m sure Ubisoft would love to hear this, but I mean, none of us loved Clancy. It wasn’t our dream license.”

After scouring Clancy’s catalog for something adaptable and finding the options lacking, Ed Byrne, Nathan Wolff, and the other New York transplants agreed they would need to make up something of their own.

“What we realized was, ‘Well, we can just put Clancy’s name on anything,’” says Byrne. In lots of cases, the licensee would take umbrage with giving an untested studio such freedom, but Tom Clancy himself showed little interest in the project. To Byrne’s recollection, his people only provided one guideline: never let the player kill anyone inside a church.

That didn’t mean the pressure was off, though. Konami unveiled Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty at E3 that spring with an almost too-good-to-be-true demo. The excitement was feverish. Ubisoft Montreal’s still untitled project had just enough shared characteristics – high-tech gadgets, espionage, contemporary political set-dressing – to be a competitor. Of course, the team, still small, inexperienced, and unproven, probably didn’t think of itself as competing with Hideo Kojima, even then a widely celebrated director. Ubisoft, however, handed word down: make the game a “Metal Gear Solid 2 killer.”

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty

Envisioning how the myriad selection of mechanics and ambitious ideas workshopped for The Drift would be turned into the next Tom Clancy game was made easier by this new constraint. If Rainbow Six and Ghost Recon covered SWAT-style tactical raids and military spec-ops, respectively, then Splinter Cell would do intel-gathering black ops. The stealth pillar stood out from the existing Clancy projects, while the Clancy name and grounded realistic world made it unique to Metal Gear.

Before Splinter Cell became the title, the team kicked around many alternatives. Echelon was the studio’s top choice for a while, but it couldn’t use it for legal reasons.

The meaning of Splinter Cell is a bit unclear, depending on which game in the series one plays (and no one interviewed for this story remembers exactly how it came about), but it stuck.

Designing Levels

Designing Levels

While the team knew it was making a stealth game, what that would look like was up in the air. A split existed between those wanting to take inspiration from Looking Glass Studios’ 1998 game Thief: The Dark Project, drawing upon its open-ended, naturalistic levels and subdued presentation, and those wanting to emulate Metal Gear Solid and its more directed, set-piece-driven approach to stealth action.

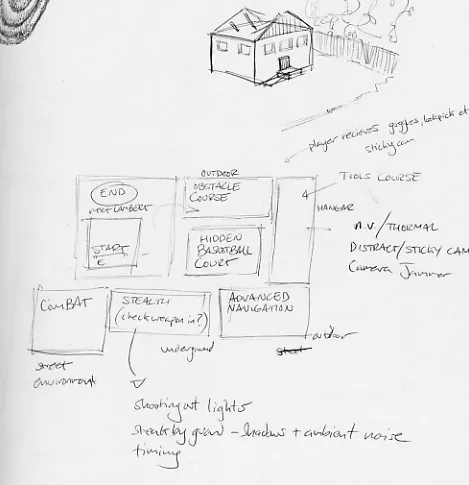

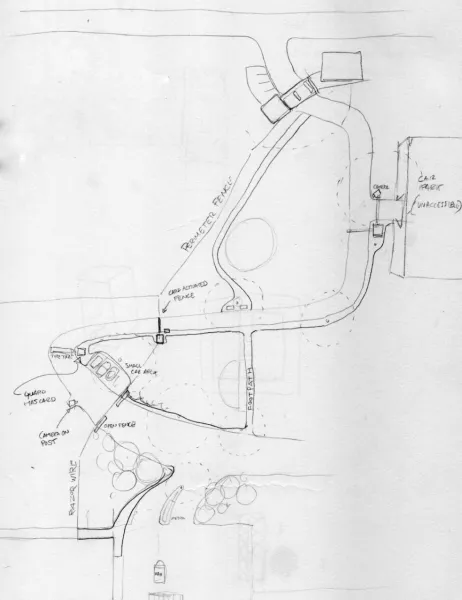

Courtesy of Ed Byrne

Design ideas from Splitner Cell’s “Training” level, which serves as the tutorial

To some degree, both sides got their way. Splinter Cell didn’t have a single director, like most games. Instead, the team divided direction into separate “packets” by pairing level designers with environment artists and having each set of two make its own stage. When played with this in mind, it’s not hard to verify – the game’s nine levels, though consistent with the overall style, each represents distinct flavors of Splinter Cell.

Ubisoft Montreal kept a “war room” where big foam core panels adorned one wall. On them, the team divided the game into story beats. By arranging notes, it could attach levels, design concepts, characters, and mechanics to each chunk of the story. Though each level design pairing had relative freedom over their section of the game, the overall structure helped keep things on track.

The Unreal engine let the team extensively use something Ubisoft’s internal OpenGL engine didn’t: dynamic light and shadow.

Earlier in development, when asked by a higher-up what the core gameplay was, the team didn’t necessarily have a clear answer beyond the basic premise of stealth. However, once the engineering team began taking advantage of Unreal’s shadows, it became clear that it would need to be considered at every level. Given that a level could only have a couple of real-time, dynamic lights due to resource limitations, most of it had to be static. That limitation worked in favor of Splinter Cell’s deliberate design, however.

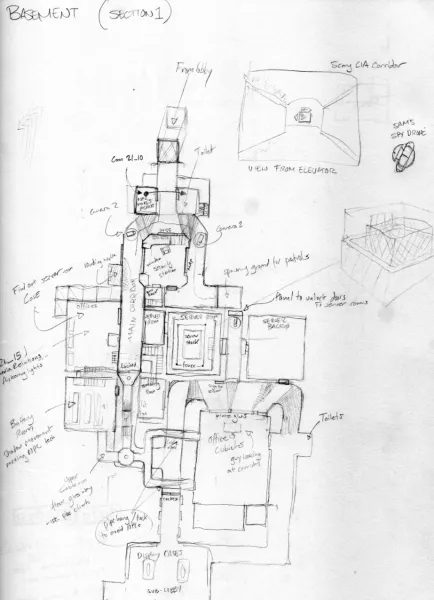

In Byrne’s design notebook, the initial draft of the “CIA HQ” level reminds one of level design circa the cartridge days: sharp lines on graph paper, with rooms and interior features scrawled in pen. The shadows, Splinter Cell’s only refuge for Fisher, are drawn by hand. From the top down, one can see the routes and vulnerabilities in security. The shadows and vision gaps Sam can take advantage of becoming like an imaginary line drawn through a maze.

Courtesy of Ed Byrne

Design ideas from Splinter Cell’s “CIA HQ” level

In-game, the artifice is harder to detect. The trick of most good game design is something like smoke and mirrors, a wild west village of false walls and facades propped up around the player to impart the impression of a place. The illusion is strong in Splinter Cell, especially for a 2002 title. The impressive graphical technology plays a part, of course, but so does the attention to detail and set dressing. Guards don’t just walk back and forth; they try to get food out of uncooperative vending machines, step outside for smoke breaks, or lounge in chairs and watch TV.

In some environments, the team made entire effects just to add interactivity and verisimilitude to one room. People make much ado about Metal Gear Solid 2’s real-time melting ice cubes, but lesser known is Splinter Cell’s fish tank which, when shot, slowly drains water from each bullet hole until the water level stabilizes. What is, on paper, a relatively simple and classically designed video game becomes, in practice, a densely atmospheric and involving experience due to such touches.

Mechanics were worked on by many but chiefly organized by Wolff.

“My role was, basically, just generating a ton of documents,” says Wolff. Every gadget, item, and method of interaction that the player has access to needed a document to describe its relevance to the game and use case. If Fisher could grab a guard and interrogate him, for example, Wolff would need to write a few pages on why the player would do that, how it would work with the level design, and what to do with it during development. Each of the individual elements could then be distilled and applied to the foam core “war room” boards for organization so that the team could create the game’s difficulty curve and pace of mechanical addition. By accumulating these documents, Wolff created a design bible for the game.

Many of the gadgets, weapons, and interactions were designed in advance of the levels. Petty, who headed the writing team and wrote much of the script, helped distribute gameplay ideas throughout the story, which, again, resulted in further tweaking of the “war room” charts.

A Lasting Legacy

A Lasting Legacy

Check any contemporaneous review of Splinter Cell, and you’ll find lavish praise directed at the game’s audio. In any stealth game, situational awareness is key. In Metal Gear Solid, at least its then-existing iterations, that mostly meant using a radar and watching patrol patterns. In Splinter Cell, however, the cogs and machinery underpinning everything are a little more hidden. Without clear, gamey cues to follow, players must take refuge in the shadows and watch as the scripting unfolds, noting where guards go, what actions they telegraph, and so on. Compared to most games of its time, you spend a lot of Splinter Cell stationary, watching. As such, the soundscape plays a key role in evoking a space.

Fabien Noel was the only member of the sound team during production. In 2001, Noel was working in France in a wholly separate field. He moved to Montreal to try applying his background to something new. He worked on Batman: Vengeance for the GBA before making his way to Splinter Cell. Noel, having specialized in the acoustics of buildings, noticed something lacking right away.

Courtesy of Ed Byrne

Design ideas from Splinter Cell’s “CIA HQ” level which ultimately didn’t make the cut, showing a proposed addition where players would escort a van out of the facility

“The first thing I realized was, ‘Wow, there was no sound propagation,ʼ” Noel says. “At that time, there was no notion of walls and doors. That when you close a door, the sound is muffled; when you open the door, it is not.” Working with the engineering team, Noel created a system that simulated the movement and dissipation of sound waves throughout the game environment, considering each room’s architecture and layout. He used a similar system to control sound levels on different types of flooring. Because the system was expensive on the CPU, Noel had to fight with the team for his share.

“I was nice aggressive, but I did not take a no for a no,” says Noel. “Sound is important; it is part of the immersion.”

Noel also directed Michael Ironside, whose gruff performance as Fisher is as iconic as the character’s design itself.

“At the beginning, it was kind of, ‘It’s just video games, so it’s not very important,’ but I think [Ironside] got attached to the character,” Noel says. “After a couple games, he was asking us, ‘When are we doing the next Splinter Cell?’”

Ironsideʼs voice was instrumental in bringing the character to life but wouldn’t have been quite so effective without Fisher’s quintessential design.

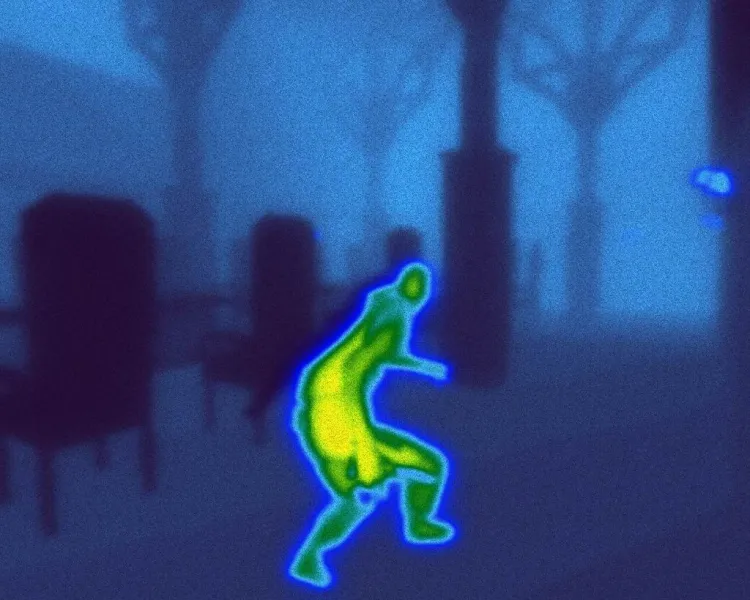

“In all honesty, I was simply just trying to come up with a design that Iʼd thought would look cool,” says Caya. He pored through military magazines, comics, and movies, looking for anything to spark an idea.

“One day, while sketching some rough ideas, I just had this cool visual suddenly pop up in my mindʼs eye,” Caya continues. “I could see the outline of a dark silhouette hiding in the shadows, and the only thing visible would be the reflection of some lights bouncing off the lenses of some night vision goggles. I instantly knew that I had found the visual foundations for Sam. Never mind that it realistically didnʼt make a lick of sense in a stealth game. I just thought it was f—ing cool.”

Splinter Cell

Others floated the idea of making Sam older and giving him some gray. Fabien Noel attached the night vision startup sound, now synonymous with the brand. Petty and company gave him the wry, detached humor and lines that exude the confidence of a man comfortably past his prime but none the worse for wear. Ironside brought him to life.

Just like any video game of its scale, Splinter Cell was made in that fashion: each element created carefully and up close before being fitted into the larger patchwork. Unlike most, however, its lack of a single director or person to make the calls made Splinter Cell more quilt-like than most. Each level, character, mechanic, and room carries the subtle seal of its unsung creator yet coheres under the team’s commitment to collaboration and compromise.

That an unproven studio made up of primarily inexperienced developers with no work history could turn the remnants of a canceled game into the makings of a bonafide console seller is nothing short of remarkable. Five sequels and over 20 years on, Splinter Cell remains an exemplary video game. Except for some cameos, it has been ten years since Fisher has seen the light of day.

One can only hope that when the old man returns in the upcoming remake of his first outing, the devs shepherding him in can replicate the passion and verve of his original creators.

“We were just these young dudes being like, ‘Hey, would this be cool? Let me draw it on a napkin,’” recalls Wolff. “If the idea works, even if itʼs from someone without a lot of experience and done in a little bit of an amateur way, the idea was solid. The idea worked.”

This article was originally published in issue 359 of Game Informer