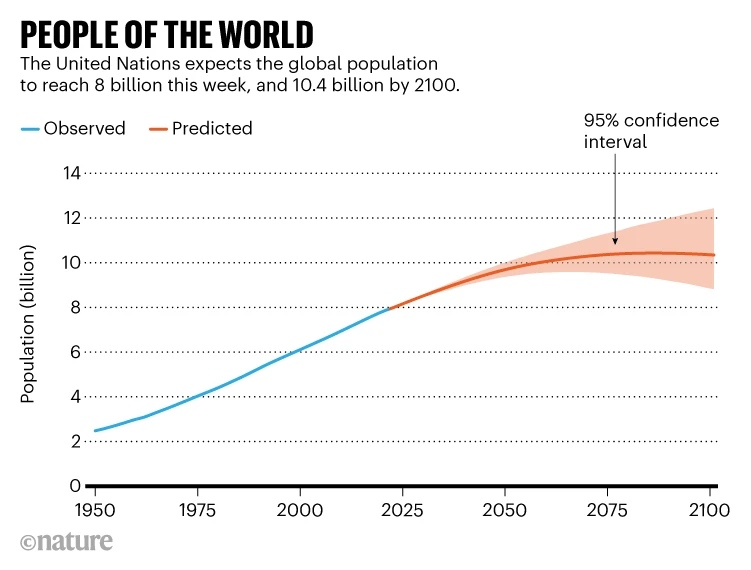

According to the models of the United Nations (UN), the world’s population will reach 8 billion today—a mere 12 years since it passed 7 billion, and less than a century after the planet supported just 2 billion people.

The latest UN population update, released in July this year, also revises its long-term projection down from 11 billion people to 10.4 billion by 2100.

Demographers will never be sure if 15 November really was the Day of Eight Billion, as the UN has named it, but they do agree on one thing. Although the human population has grown rapidly, that growth is slowing—and, within a few decades, Earth’s population will begin to shrink.

“It is a crude approximation that is more of a symbolic finding,” says Patrick Gerland, who leads demographic work at the UN Population Division in New York City. “We may have passed it, or it may be a little later, but it’s around this time that humanity is reaching 8 billion.”

Although approximate, this could be the most reliable estimate that the UN has produced so far. The organization recently changed how it analyses data, switching from five-yearly to annual intervals. And there has been a steady improvement in recent decades in the ability and capacity of many countries to collect statistics.

Significant blind spots remain, however, particularly for countries that are experiencing humanitarian crises and conflicts, such as Somalia, Yemen and Syria. “The accuracy of the underlying, empirical information varies tremendously around the world,” Gerland says.

Differing estimates

The rapid rise in population throughout the twentieth century (see ‘People of the world’) was driven by advances in public health and medicine, which allowed more children to survive to adulthood. At the same time, fertility rates (defined as the number of children per woman) stayed high in lower-income countries.

Demographers take a particular interest in fertility rates and how they are expected to change, because these factors help to drive what will happen to the global population in the future. Differences in assumed fertility rates have been an important reason behind a notable diversion in what various models had previously forecast for the world’s population in 2100, for example. Those results suggested a spread ranging from 8.8 billion to nearly 11 billion by the end of the century.

“If you make even relatively small adjustments in these fertility-rate trajectories it accumulates, and suddenly a big country can have 100 million people more 80 years from now,” says Tomáš Sobotka, a population researcher at the Vienna Institute of Demography.

In 2018, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Vienna forecast that global population would be about 9.5 billion in 2100. The institute is now preparing an update, which will raise that estimate to between 10 billion and 10.1 billion. The change is due to higher observed and expected survival rates among children in lower-income countries, Sobotka says. Another factor is higher estimates of fertility rates in some large countries, including Pakistan.

More reliable data

The most significant factor behind the UN’s updated forecast is that data from China has been more reliable since the end of the country’s one-child policy in 2015.

“There was always a mismatch in the different sources of data coming from China during that policy,” Gerland says. Some parents, particularly if they had a girl, would not register an initial birth, he says. For that reason, many children did not appear in official statistics until they started to attend school. “We basically had to rely on education statistics for more accurate information,” he says.

The UN predictions suggest that China’s population has already peaked and will now shrink year-on-year until at least the end of the century.

“The Chinese statistics are suggesting there are already more deaths than births in China, and in that situation the population will start to decline,” Gerland says.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on November 15 2022.