It’s been a year since global leaders renewed their climate pledges at the landmark summit in Glasgow, UK. Next week, they’ll convene again in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, during the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP27) to carry on negotiations aimed at reining in global warming. But the world is a different place now: leaders will need to confront the energy crisis spurred by the war in Ukraine, and mounting damages from extreme weather events.

The short-term outlook is daunting. Energy prices are skyrocketing in Europe and beyond, spurring a new round of government investments aimed at artificially reducing the cost of fossil fuels. By one estimate, such subsidies nearly doubled in 2021 and are poised to jump again this year, which will only increase dependence on the world’s dirtiest sources of energy.

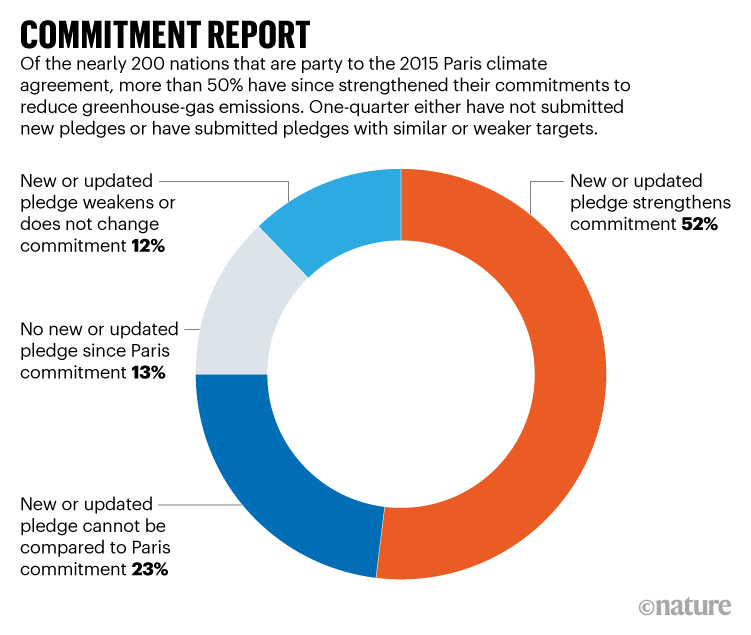

But there is good news as well. Renewable-energy installations continue to rise globally. And some 26 countries have made new climate commitments this year (see ‘Commitment report’), including Australia, which pledged to curb greenhouse-gas emissions to 43% below 2005 levels by 2030. An International Energy Agency analysis suggests that new policies announced by the United States, Europe and others in response to the energy crisis are poised to spur investments in clean energy, potentially enabling a global plateau in emissions by 2025.

Meanwhile, the impacts of climate change are mounting. In September, scientists announced that global warming helped to fuel the unusually heavy monsoonal rains that caused extreme flooding in Pakistan this year, killing more than 1,700 people and causing tens of billions of dollars in damage to homes and infrastructure. Arguments over how to pay for such devastation will be front and centre in Sharm El-Sheikh, as will questions about whether wealthy countries are doing enough to help poorer countries adapt to global warming.

“Mitigation and adaptation: those are the two issues” at COP27, says Joyeeta Gupta, a political scientist at the University of Amsterdam.

Loss and damage

Aware that industrialized countries bear a large amount of responsibility for the warming that is already causing droughts, floods and fires across the world, low-income nations have spent more than a decade pushing for compensation for damages. In particular, they want a loss and damage mechanism by which wealthy countries help poorer ones to pay for the impacts of global warming, which are now unavoidable. Those efforts are gaining traction.

In Glasgow, countries agreed to establish a dialogue on the topic, but the major negotiating blocks representing low-income countries are calling for action in Sharm El-Sheikh. “This is the one area that has been completely neglected in the negotiations,” says Tasneem Essop, who is based in Cape Town, South Africa, and who is executive director of Climate Action Network International, a coalition of advocacy groups. “Now it is on the political agenda.”

Few expect a resolution, because the United States and other high-income countries have steadfastly opposed writing what they fear would be a blank cheque to cover all manner of future climate damages. But it’s possible that a new mechanism could be created at the summit for providing financial aid when specific climate-related disasters strike, says Danielle Falzon, a sociologist at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

“Establishing some kind of funding mechanism is really important, because people are bearing the cost of loss and damage right now,” Falzon says. If it doesn’t happen at this year’s COP, she says, it’s just a matter of time, because low-income countries have made the issue their top priority.

Loss and damage is just one piece of a larger discussion about how to improve funding for climate adaptation in low-income countries. In Glasgow, wealthy nations agreed to boost funding for adaptation but they have fallen short of their goals. One of the tasks in Sharm El-Sheikh is to craft better standards that can be used to track investments, to ensure that monies are well spent, Falzon says.

Curbing emissions

More than 150 countries submitted fresh climate pledges last year, and the Glasgow Climate Pact that came out of COP26 requested that countries submit fresh pledges this year. Under the agreement, the United Nations will now evaluate those pledges on an annual basis. Furthermore, the formal process of assessing progress on climate goals — a ‘global stocktake’ required every five years under the 2015 Paris agreement — is now under way and will be on the agenda in Sharm El-Sheikh.

In addition to the 26 countries that have already made new commitments this year, several are expected to weigh in during COP27. If countries make good on all these commitments, as well as those put forward in Glasgow, carbon emissions could drop by an extra 5.5 billion tonnes annually by 2030, according to the World Resources Institute (WRI), an environmental think tank based in Washington DC.

That is akin to eliminating a whole year’s carbon emissions from the United States, the world’s second largest emitter. But it still falls far short of what is needed to achieve the goal set out in the Paris agreement: to limit global warming to 1.5–2 °C above pre-industrial levels. If countries follow through on their pledges, global warming could be limited to around 2.1 °C of warming by the end of the century, according to Climate Action Tracker, a consortium of scientific and academic organizations. Without those pledges, the consortium estimates that the current laws and policies put the world on track for around 2.7 °C of warming, which scientists say might lead to some catastrophic climate impacts.

“We’ve made some headway, but the pace is not yet what we need it to be,” says David Waskow, who heads the WRI’s International Climate Initiative.

In Sharm El-Sheikh, countries are also expected to begin fleshing out a new ‘mitigation work programme’. Precisely what it will consist of is unclear, but one possibility is that it will focus on how nations will meet broad emissions goals, by setting targets for specific sectors, such as electricity, transport and agriculture.

For any of these efforts to be useful, a sharper focus on accountability is needed, Waskow says. “We can’t just move on to new commitments without getting a grip on whether the current commitments are being carried out.”

For Gupta, a big risk for negotiators at COP27 is getting bogged down in procedures: “I’m afraid we’ve gotten so lost in the details of these COPs that we’ve lost sight of the main thing, which is that we have to get rid of fossil fuels.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on November 3 2022.